Bah, Black Sheep.

Spoiler alert: The little boy in the song was Cupid.

"Black sheep", as a negative epithet, has a much more complicated history than one would originally assume. No two people seem to use it the same way. It's a bit like a Rorschach test. It says a lot more about you, than about the person.

If you call a family member a "black sheep", you may mean that they are a murderer, a conman, a cheat, filled with vice and folly, incompetent, estranged, or simply, different.

On the positive side, I did discover the origin of Bah Bah Black Sheep, so that was fun.

The Black Scary Sheep of the Family

The Oxford English Dictionary credits a story by G. J. Whyte Melville with the coining of the phrase of familial “black sheep” in 1856. They are a bit late, thought.

If you were to read New York Times articles from the late 19th and early 20th century, you’d see the term used to describe situations of homicidal siblings or scions of wealthy families who resort to the thievery.

One 1905 headline reads: “BLACK SHEEP, BROTHER SAYS, And Advises the Jailing of Edward Brown, the Pistol Hold-Up Man.”

In 1907:

“Black Sheep of Rich Family - Police Were About to Arrest Him When He Was Killed as a Burglar.” “Hoffman, it is believed, came of & prominent German family. He was a man of refinement and had been in the German army.”

And in 1911, the headline of

“SCHEIB'S MOTHER TO AID HIM. Though She Calls Him a Black Sheep, She Comes to His Defense.”

“Henry was what everyone called a ‘black sheep.’ He left our home in Chicago ten years ago, and I suppose I have heard from him more than three or four times in all those years. Then he usually wanted money.”

New York Times, June 2, 1911

(He was quite a baaaad boy; Scheib was charged with murdering his wife.)

On other hand, it seems to be synonymous with the Prodigal Son.

Viceful, not vicious

In 1872, there was an article in London Society:

“Mirabeau: the Black Sheep and the Great Man.”

It was in the year 1783 that two noble old men, splendid in appearance and magnificent in manner, who looked as it they had been forgotten by the century before and left as types of a better and more refined age. wet together to hold & family council upon a black sheep - a prodigal son, who, after having passed through an early youth distinguished by every vice and folly, had appeared before them as a penitent… The great man of 1791, was the black sheep of 1781.

via New York Times, October 6, 1872

In 1833, the Chamber’s Edinburgh Journal, printed and distributed in multiple countries, ran an editorial on their front page. The black sheep are the ones frivolously spending people's hard earned money on vice and folly.

This is actually the original source of the sentiment of the phrase "every family has a black sheep".

“Makers and Spenders”

...A few of us are industrious to the excoriation of our fingers, and the dizzying of our heads; but, by reason of our very application, we have neither time nor taste to spend the result: it goes to provide senseless luxuries to persons who are some way or other connected with us, and who, rely. ing more upon our resources than we are ourselves disposed to do, permit themselves to have abundance of both time and taste. Who do you think keep up the deep heeled boots, and the handsome clothes, and the cigars that are smoked on our fashionable streets? —not, to be sure, the smockfaced fools who wear and whiff them. Who do you think support the fine fancy taverna, which, under the monkey names of cafés, and saloons, and divans, now ornament our cities?-not, to be sure, the strutting coxcombs who frequent these places, and think they are enjoying life. It almost all comes out of the pockets of industrious fathers, brothers, and other oppressed relations, who would be shocked at nothing so much as to be told that they supported such follies.

In short, this monster hangs like a leech upon the family, till all that it has made from youth to age, and perhaps its original patrimony besides, is fairly drained and dribbled off through the channel of his base debaucheries. Such is not certainly the general extent of the evil; but that it is always more or less so, every family in the country, above the condition of labourers, and beneath that of the aristocracy, will attest.

It seems as constant in nature that every household should have its one or more black sheep, as that every nest should contain a bird smaller and feebler than the rest.

Chamber’s Edinburgh Journal, September 7, 1833

In 1911, there is an article in which the writer overhears a group of young men talking:

AS A BLACK SHEEP SAW IT:

Never Was Educated in Anything but Spending Money for Pleasure

...It used to give him a lot of pleasure to see me right in the front of the bunch and holding the pace. I'm not sure that wasn't one of his ways of showing off. I never had the bit put on me until last month. Now I wake up to the fact that all the training the governor ever gave me was to spend money for these things and that's all I know how to do. If I start anything now-at thirty-why I go in with a great big handicap.

New York Times, July 23, 1911

The Evolution of the Familial Black Sheep

The euphemism has evolved which means something between “family bad boy” to "family odd duck”, the family member who marches to the beat of their drummer, putting it nicely.

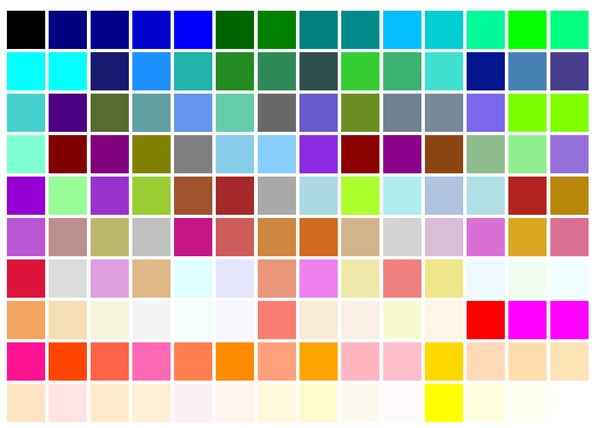

As you can see, the sheep color has evolved to simply describe the other, all sheep are white, and the black sheep just standing out.

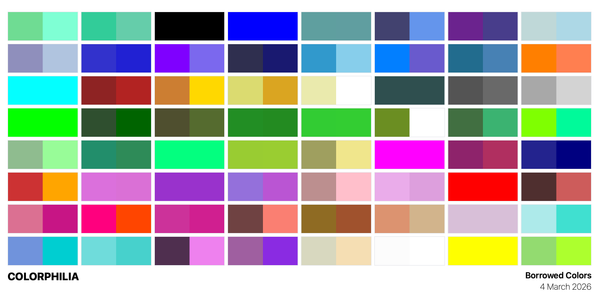

This phrase evolved to include colors. Fashion designer Alexander McQueen famously said “I’m the pink sheep in the family.” From there, you can buy t-shirts on the internet, “i’m the rainbow sheep in the family” and the like.

It’s a similar linguistic phenomenon to to “-washing”, which began talking about the actual act of whitewashing that Tom Sawyer tricked his friends into doing, to greenwashing, pinkwashing, and more.

Generally Bad Black Sheep

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

When you read an article like this about avoiding the draft by hiring substitute, it makes some it feel like it is about misrepresentation.

The substitutes, as a class, are a fine-looking set of men. It is true there are some “black sheep” among them, and for these all the good men have to suffer, as a string guard is maintained over the whole party. Many of those who have gone as substitutes have been mechanics out of employment, who have adopted this method of aiding their families.

New York Times, August 18, 1863

Black Sheep Conmen

Or as a conman.

“A Black Sheep Captured Far Away”

He is charged to have forged… a promissory note. His business is school teaching, composing, book-keeping, and surveying; is a good talker, but seldom looks you in the face; is a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and a regular attendant, was an active member in the Young Men’s Christian Association; is strictly temperate.”

San Francisco Call, November 11, 1883

“He is a Black Sheep”

He came to Kansas with bushels of credentials. and scores of notices telling what a glorious record he had made in Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana. In nearly every town in the State Wade made one one or more temperance speeches, getting into a little disrepute, however, in one or two places by having some zealous brother smell the taint of whisky upon his breath… He is a young fellow about 32 years of ago, of good address; and calculated to make a good appearance. His impostures have been eminently successful, and he will be recognized all over tho State by the description we have given of him. He will probably seek other pastures when his time is out here, and again assume the role as preacher and lecturer.

New York Times (From Atchinson (Kansas) Champion) August 8, 1878

Corrupt Black Sheep

Other times, it’s about corruption:

And it is cruelly unjust to make the charge indiscriminately; because of a certain cumber of black sheep. be it small or great, the whole flock should not be condemned. That the Senate and the Assembly embraced true and honorable men, no one can dispute; and if all were not, I am persuaded that by far the larger proportion were not only honest, but wholly free from reproach. An unequaled willingness to be corrupted, in certain instances, has unquestionably existed, and this fact has.

New York Times, April 26, 1863

Corrupt “black sheep” politicians even receive backhanded compliments.

“Black Sheep Commended”

These candidates have secured, without apparent difficulty, the recommendations of scores of members of Congress and other men in public life. Their testimonials are numerous and impressive. Many a man who has held public office and never been false to his trust might strive in vain to procure such an array of recommendations as these black sheep exhibit.

New York Times, March 30, 1889

In 1897, there is even a “defense of black sheep” written by the Boston Congregationalist:

Why is it that a black sheep is so apt to attach to himself the sympathies of some very respectable people? When we consider how critical the average modern church is of a man's personal and pastoral qualifications, even when his character is as pure as gold, it seems a marvel that bad men who creep into the ministry should succeed in getting decent people to indorse them, ministerial associations even temporarily to harbor them, and churches to pass flattering resolutions in regard to them.

via New York Times, March 21, 1897

Untrustworthy Black Sheep

But before familial black sheep, black referenced something more “untrustworthy” or “not honest” in England. It is assumed that the connection comes from Jacob manipulating Laban’s sheep to make them black and multicolored in order to amass his own fortune.

perhaps originally with allusion to Genesis 30:32, where Jacob selects ‘all blacke shepe amonge the lambes’ (Coverdale 1535; perhaps after German alles, was schwartz ist vnter den lemmern (1523 in Luther's earliest draft of his translation of Genesis; 1545: alle schwartze schafe)); note, however, that German schwarzes Schaf is not securely attested in the figurative sense before the 19th cent.

OED

Which made it a family ordeal.

English Sheep

There was a common Latin phrase used during the 17th century, Nigro carbone notandus, which was translated in a school primer as “marked for a black sheep” for untrustworthy people in the late 17th century. But that doesn’t exactly mean “black sheep”, it means “black coal”.

The usage of this phrase apparently goes back when they would color the hands of the untrustworthy people black with coal, so you can recognize them. Whatever the origin, they would transfer the usages of Nigro carbone onto black sheep.

Religious Sheep

But the borrowing of the phrase seems to be uniquely English and Protestant.

I cannot prove it, but I have a theory that Nigro Carbone sounds a lot like a black sacrifice: Corban is the English borrowing of the Greek's borrowing of Korban (sacrifice) from Hebrew. Jesus was known as the Angus Dei - Lamb of God, and portrayed as a white lamb. The sacrifice of black sheep was pagan in nature, to other gods, like Mars, and to the underworld.

The mere act of a sacrifice of a black sheep was a profane act, not sacred. Which means that while the mention of "black sheep" may theoretically reference Jacob's actions, the Nigro Carbone as the black sheep was the anti-christ.

White Flock, Untrustworthy Black Sheep

But not everyone thought this way. As Thomas Shepard wrote in The Honest Convert wrote around 1640:

“Cast out all the Prophane people among us, as drunkards, swearers, whores, lyers, which the Scripture brands for blacke sheepe, and condemnes them in a 100 places.”

He probably was a lot closer to a Quaker, though, and the Quakers seemed to have an affinity for the term. The OED's first flock-related black sheep was in 1815:

A quaker! ah! there are black sheep in all flocks.

R. F. Jameson, Living in London i. iv. 20

In every organization, be it religious, professional, or governmental, there are the people are the proverbial rotten eggs of the bunch.

Military Sheep

In England, and in the United States (both in the North and South), before, during, and after the Civil War, the concept of “black sheep” were always used to deserters or untrustworthy soldiers, similar to the members of parliament or politicians you could not trust.

Irish Sheep

In the military context, we begin to see quotes from people who refused to join Irish nationalistic groups as “black sheep”.

At first glance, it reminded me of an event in 1648 where, according to a rather inciting book, a Catholic slaughters a black sheep and hangs it up in a Protestant church in Dublin. For a Protestant audience, this would signify the above mentioned anti-christ.

In some later Irish dictionaries, “colonizers”, “outsiders” and “black sheep” would be synonymous, and used to translate the same word. But I don’t think that’s what the epithet of “black sheep” used against the ones who didn’t want to join the Irish nationalistic cause meant.

The Irish have many words for sheep because they had a lot of sheep. They were particular in their language. In 18th century Irish, there was a saying translated as “one scabbed sheep will mar all the flock.” It's not different, it's diseased, and therefore a danger to the flock.

(As the sources for the “black sheep” epithets in Ireland were in English papers, I don’t actually know what phrase was used in Irish.)

French Sheep

It was similar to the French version of the epithet “black sheep” is brebis galeuse, meaning the same thing, “scabby sheep”. Their idea was that one infects the entire population.

In fact, the concept of "scabs" has become the language of union members to describe non-union members.

We do know that the French, too, did have a distinction between black sheep and scabby sheep. Voltaire, in his 1764 Philosophical Dictionary, in his section on “Superstition” used brebis noires (literally “black sheep”) when talking about how the ancients would sacrifice black sheep out to gods for forgiveness from sins like murder.

Baaahck to Black Sheep

Which brings us the 1744, when a Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book was released with English children’s songs, including "Bah Bah Black Sheep".

Bah, Bah, a black Sheep,

Have you any Wool?

Yes merry have I,

Three bags full,

One for my Master,

One for my Dame,

One for my Little Boy

That lives in the lane.

There are many theories and conspiracies about what this referred to, but it wasn’t either racist, have to do with a 18th century wool tax, or have anything to do with untrustworthy people.

I discovered an article written in the Philological Society of London’s 1787 The European Magazine and London Review recounting a meeting of the society, which contextualize it.

The first English printer, in the 15th century was a man named William Caxton, who was responsible for publishing Chaucer’s Tales, among others. He also translated texts from other languages, one being originally from Greek, but apparently through French.

Blete, goode black shepe, b'ete,

Tel me what offeringe does thou

bringe of wole:

Gode parcels three complete.

Schal I paie myne yerly tribut meet

and ful.

An is to gif my martial maister

Joie,

And an Schall be a pillowe for my Dame ;

and an to playe the prettie boye

that carolleth in the lane.

There is an entire article about how Caxton mistranslated the French, which mistranslated the Greek. But they explain that it’s about a yearly tribute of wool to Mars, Venus, and Cupid. The philologist continued that the correct translation of the song would probably be:

Baugh, baugh, black sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, I have plenty,

Three bags full:

One for my master,

Another for my dame,

And one for the naughty boy

that’s crying in the lane.

They conclude with the admission of the "sagacious absurdities" that academics would waste their time analyzing nursery rhymes. But then the scholar concludes by misquoting Phaedrus saying that:

the motto of every scholar ought to be Nisi utile est quod facimus, stultitia est. (Unless what we do is useful, it is foolish.)