The Chinese (India) Ink Story

or "How reliance on advances in technology impedes innovation."

Last week, one of the proprietors of Paper and Pencil in Chicago asked me if I had researched ink yet. When I was researching the history of red ink, I happened to learn quite a bit about ink, but I hadn’t researched it in a structured way.

Then I discovered how complicated ink was. So I decided to begin with a single ink, India Ink, known in French as Encre de Chine, or Chinese Ink. It seemed simple enough.

What I discovered was how much untold and unknown experimentation and innovation needed to have transpired in China over millennia to create the resulting ink.

The History of Ink

Four millennia ago, the story of ink began.

Carbon-based Ink

Most ink was carbon-based, meaning as a result of soot or some burnt material, some glue or binding material, like resin, and some liquid, like water. The art of ink making continued through the Egypt Kingdoms and the various Greek Empires, and during Roman Empire.

One of those ways was by using Cephalopod ink, but that's a different piece.

Iron Gall-based Ink

During that time, they also discovered that if you dissolve metal in an acid, it oxidizes, and if you use a binder, you would be able to write with it, an have it virtually permanent. Gall is an acidic resin, called ‘afs in Arabic or Aramaic, which when combined with vitriol (created from iron and sulfuric acid) would create this iron gall ink. Some combination of this would be used until the 19th century when sulfuric acid would be replaced with hydrochloric acid.

Opportunities for Experimentation

With carbon-based inks, people in different periods and locations would experiment with switching up the various ingredients, sometimes burning bones making ivory black, burning lamp for lampblack, and burning regular organic material for a regular black.

For example, the Talmud notes that olive oil smoke was the optimal way of making lampblack ink. That same source reports that balsam sap is the best binder or mucilage to use.

Maimonides, the 11th-12th century Jewish scholar, philosopher, and physician, born in Spain and moved to Egypt, and wrote a book of law as a simpler replacement to the Talmud. In it, he explains the ink-making process:

You gather smoke of oils or tar and wax and similar objects, and combine them with tree sap, mix in a little honey, moistened, and crushed until flat cakes, and then dry them, and store them. When someone wants to write something, they can put that into gall resin and write. This is erasable. This is the ink with most preferable to write [Jewish texts]. If someone used gall resin with vitriol (made by iron and sulfuric, thereby making an iron gall ink), it is also acceptable.

Mishnah Torah, Laws of Tefillin, Mezuzah, and Sefer Torah 1:4 (my translation)

Besides for the addition of the honey, it seems to be a very similar to the Talmudic description and early versions of carbon inks. More than honey being just a nice symbolic addition, the idea that the glue could always be improved seemed to be still alive. It's also interesting to note that gall resin would be used as an additional binder at the time of writing.

Sorry, we're too busy building telescopes

But as one scholar of ink wrote:

In the Middle Ages both the carbon inks and the iron gall (iron tannin) inks appear to have been in common use, although it is thought that the iron gall inks were most generally used as the secret of making a satisfactory carbon ink was gradually lost.

David Carvalho, Forty Centuries of Ink, 1904

(Emphasis added)

And that’s what happened in Europe.

The Chinese Tradition of Ink

But in China, having began developing in around the same time as Greece, they continued optimizing their ink through the years, turning the creation of carbon inks into an art form. For internal Chinese use, they turned the ink into sticks, and had an-ink stone filled water that they would use to moisten the end of the stick while writing.

Attempts to steal trade secrets

Between the 17th and 20th centuries, scientists and manufacturers in Europe and the United States attempted to reverse-engineer or copy India or Chinese Ink, which was such a good ink, it is said that a document could be submerged in water for weeks without erasing the ink.

Throughout the 19th century, there are numerous articles in places like Scientific American trying to ascertain the process. For example, in 1847:

Ink equal to China or India Ink may be made by dissolving six parts of isinglass in twelve of water, one part of Spanish liquorice in two of water, mixing them when wam and incorporating gradually with them one part of the best ivory black, stirring well. When the mixture is complete it is to be heated in a water bath until so much of the water is evaporated as to leave a paste which may be moulded into any required form.

“The College Courant” in 1870 wrote:

The basis of all the different kinds and qualities of India Ink is lamp-black, the best of which is obtained from pig's foot and other oils, and sometimes from resins, while an inferior sort is made from pine wood. The materials from which the lamp-black is to be derived are burned in a furnace about a hundred feet long, along the sides and top of which the smoke condenses, that most remote from the fire and nearest the top being the finest, and is carefully kept separate from the rest.

Glue made from the skin of the buffalo of the country is soaked in water for a time until it is much swollen, and afterwards completely dissolved. The lamp-black is then introduced and worked in, until it forms a soft paste. When the materials are thoroughly mixed a quantity of the oil of peas is added, and the temperature maintained for a time, at from 110 to 140 degrees. until the paste is homogeneous in character.

The peculiar odor of India ink is produced by adding to it, during the process of preparation, a mixture of Borneo camphor and musk. Only the finer qualities, however, receive this addition.

Revealing the process

In 1398, a Chinese scholar named Chen-Ki-Souen wrote a book about the process of making ink, but it was unknown to the West until it was first translated to a European language in 1882, as L’encre de Chine, son histoire et sa fabrication, translated by Maurice Jametel explaining the history of the process.

Scientific American in 1883 gives an overview of the book that:

It was not until 200 or 220 B. C. that they began to make an ink from soot or lampblack.

The soot was obtained by burning gum lac and pine wood… In the manufacture of lampblack nearly everything is used that will burn. Besides pine wood we may mention petroleum, oils obtained from different plants, perfumed rice flour, bark of the pomegranate tree, rhinoceros horn, pearls, musk, etc… The binding agent plays the chief part next to the lamp-black; ordinary glue and isinglass alone are now used. An old times glue made from the horns of the rhinoceros and of deer was employed.

According to Scientific American’s read, progress stopped for the Chinese as well.

The most celebrated ink factory in China is that of Li-ting-kouëi, who lived in the latter part of the reign of Tang,… The lest of its authenticity consisted in breaking up the rod and putting the pieces in water; if it remained intact at the end of a month, it was genuine Li-ting-kouëi. Since the death of this celebrated man there 'seems to have been no perceptible advance made in the manufacture of India ink.”

I'm not too certain how true that was. All the evidence really points to the opposite.

Corporate Espionage by Scientific Discovery

Finally, a decade later in July 1894 Scientific American makes a scientific announcement and surprisingly praises scientific discovery.

How the Chinese Make India Ink

After many unsuccessful efforts to worm the secret of the manufacture of India ink out of the Chinese, science is finally to have the last say upon this product of the Celestial Empire.

Gunpowder, porcelain, crackle-china, green indigo, and, in fact, all the very ancient Chinese products have been unveiled to us by science only; and it is science again that is to teach us how the Chinese manufacture their celebrated ink...

It has always been thought up to the present that the Chinese manufacture their ink by grinding a special lampblack, unknown to Europeans, with a suitable mucilage discovered by them, and that the paste obtained is allowed to dry slowly like their porcelain.

The light that has just been thrown upon this subject is due to the progress that has been made in micrographic studies in recent years. In fact, upon submitting a very dilute solution of the most celebrated India ink to an examination by a very powerful microscope, it has been discovered that the particles of carbon forming the basis of the ink are of a uniform diameter.

Upon repeating such examination with inferior or counterfeit India inks, it is observed that the particles of carbon are of very variable and sometimes even disproportionate diameters. Upon submitting to such control all the numerous varieties of lampblacks, it is found that none possesses this regularity of the atoms. The blacks that most closely approach it are those that have been comminuted during the manufacture and the lightest portions selected. Nevertheless, the diameters of these are still more irregular than in India ink.

This first point established, a second remained to be fixed. Is the mucilage (glue) employed by the Chinese simple or compound? Thanks to the principle established by Mr. C. Kœcklin, and mentioned by Mr. Schutzemberger in his Traité des Matieres Colorantes, we know that two mucilages of opposite nature reciprocally thin one another upon being mixed, and in proceeding by elimination, after analysis, we find that the compound mucilage employed by the Chinese unites in itself about the extremest thinness of the Kœcklin principle.

An India ink having been prepared according to these data, in a state of solution, and left at rest for one or more months and then decanted, it was observed that the particles of carbon more and more closely resembled those of the genuine India ink. Upon afterward allowing this liquid ink to concentrate and evaporate in a vacuum, there is finally obtained a plastic substance which, when dried, has all the characters of the best India ink.

(emphasis added)

It should be noted that the article didn't explain what was used for the lampblack, probably because their assumption was that the binder was more important. If anything, the discovery explained why the process worked, not what the original process was. In other words, they learned how to create better forgeries.

Shiny Ink

A 1931 “Story of Ink” explains

Carbon inks, known commonly as China and India inks, are both essentially made of very finely powdered particles of lampblack, a form of carbon, held together by some kind of glue. The China ink used mainly in China is manufactured in the form of sticks or cakes which are rubbed down in water for use with small brushes instead of pens. India ink is procurable in liquid form and is made by mixing gum arabic, shellac, and borax, with carbon in suspension.

Camphor is sometimes an ingredient of India ink, also. The borax reacts with shellac to form a kind of soap which is soluble in water, but which after drying forms an insoluble film on the paper.

This author completely conflates the concept of "carbon ink" with the Chinese variety, which could be problematic. Carbon ink needs three basic ingredients, and can be erased in water. Chinese ink doesn't.

It's important to mention that these ingredients listed in these inks are all naturally occurring substances.

- Gum arabic is the sap from the acacia tree and was mentioned in the Talmud.

- Camphor is found of the wood of various trees, was used as the plasticizing agent in making early plastics.

- Shellac is secreted by the lac bug and scraped from the bark of trees.

- Borax is naturally found in dry lake beds, and is a component of glass, enamel, and pottery glazes.

Other sources of materials for the glue would include gelatin created from fish bones or other animals.

Some of these ingredients, like shellac, feel more at home when we are talking about paint, not ink.

And that seems to have been the Chinese innovation: setting a layer of shellac, plastic, and glass to protect the lampblack carbon. It's not just about making a better glue.

I had seen sources from antiquity where they would go purposely get soot from the glassmaker's ovens, which may indicate the existence of silica in the carbon, which would theoretically have a similar effect. They knew innately that this worked better than other soot for carbon, but couldn't explain why. (I'm not a materials scientist, the connection just jumped out.)

Gum and Gelatin

Carvalho had hypothesized three decades earlier in Forty Centuries of Ink:

The answer must lie between the vegetable product known as gum and the animal product known as gelatine. The first disintegrates, quickly absorbs moisture and gradually disappears, while gelatine (isinglass) "contains under conditions 50% carbon, although its molecular formula has not yet been determined.”

And concluded:

"Indian" ink, except for specific purposes, belongs to the great past and will so continue with its virtues unchallenged and proven, until some solvent is discovered for the carbon which forms nearly the whole of its composition, at which time the perfect ink can be said to have been discovered.

Science versus Art

While Europe was content on using iterations of iron gall ink, it seems that China was experimenting with every conceivable mixture of ingredients to created lampblack, and then every single conceivable material to create complex compound mixtures for the binder, and perfecting the drying process.

The only real improvements the Europeans had done were to switch to hydrochloric acid (so as to stop ruining documents in the long-term) and adding a plant-based dye like indigo, so it would write in a strong blue color, but then, upon oxidization, dry black.

Europe considered ink a science experiment you could do at home, and China treated ink like an art. In that same vein, Ainsworth Mitchell gave a series of lectures to the Royal Society of Arts in 1922 and included this description:

The entire process of making Chinese ink, from the preparation of lamp-black to the moulding of the mixture of glue and black, is shown in these illustrations, some few of which are shown upon the screen. I think it will be generally admitted that, apart from their technical interest, these remarkable drawings, like much of the Chinese work, are most beautiful in design, full of vitality, excellent in composition and skilfully drawn.

Fighting with Ink

To end with two thoughts about ink from the West:

Go write it in a martial hand ; be curst and brief ; it is no matter how witty, so it be eloquent, and full of invention ; taunt him with the license of ink ; if thou thou'st him thrice, it shall nor be amiss ; and as many lies as will lie on a sheet of paper, although the sheet were big enough for the bed of Ware in England, set 'em down ; go, about it. Let there be gall enough in thy ink, though thou write with a goose pen, no matter: about it.

Shakespeare, Twelfth Night III, 2

and

Never argue with a man who buys ink by the barrel.

Attributed to Mark Twain and others

Have gall and buy your ink from Costco.

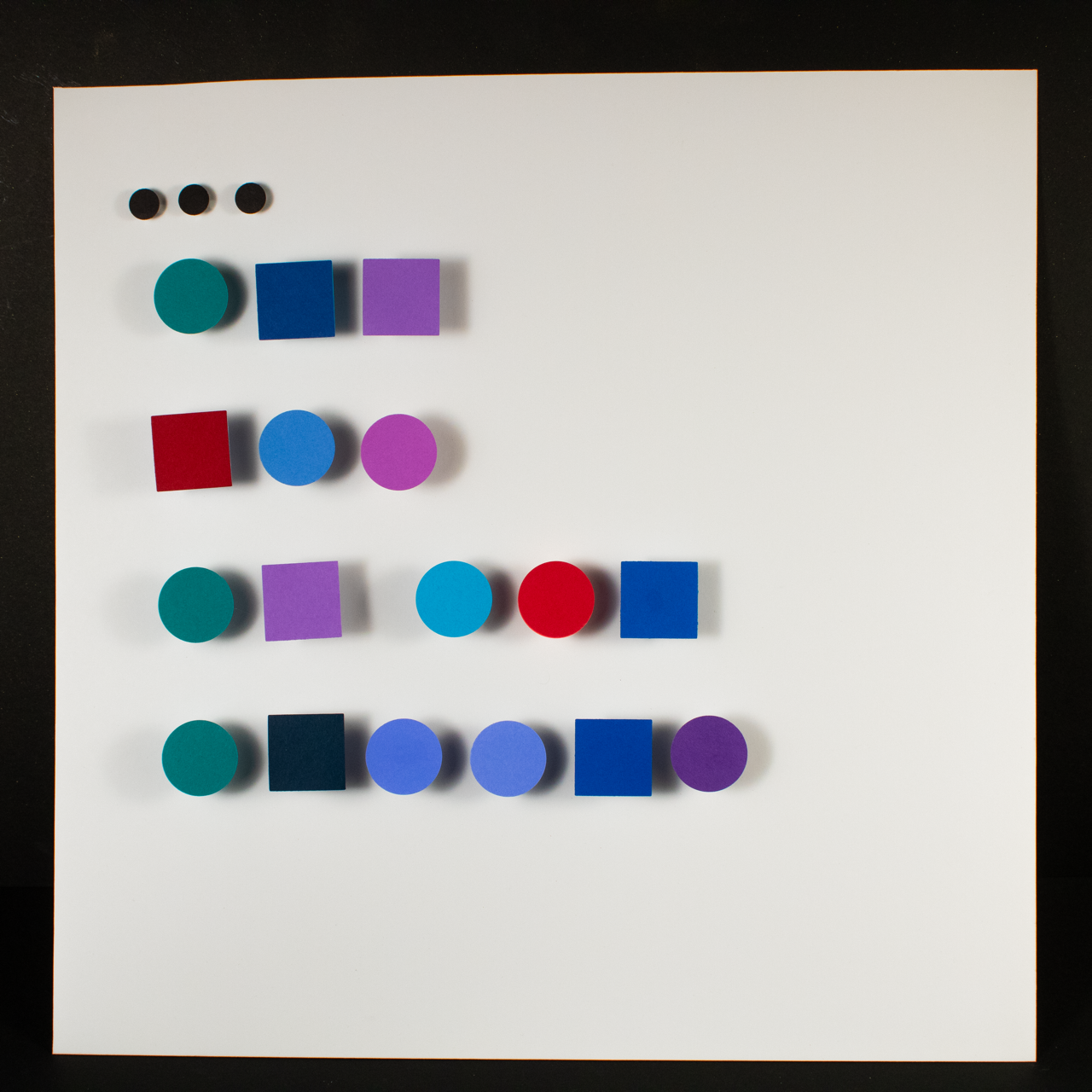

Art without Ink

In my recent Ellipses (...) collection, inspired by the second quote, I created this piece titled "... buy ink by the barrel":