So, I was wrong about oranges.

Who knew that a simple word could be so complex.

It turns out that medieval Jewish translators and the Hebrew aleph-bet play a role in how the orange got its name.

One of the things I love about studying history and language is when one is better are able to trace the evolution of a term by having some external knowledge that isn’t necessarily completely obvious.

But first, some tea.

Chai Tea

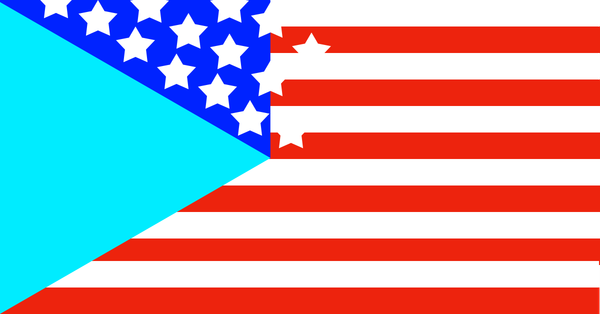

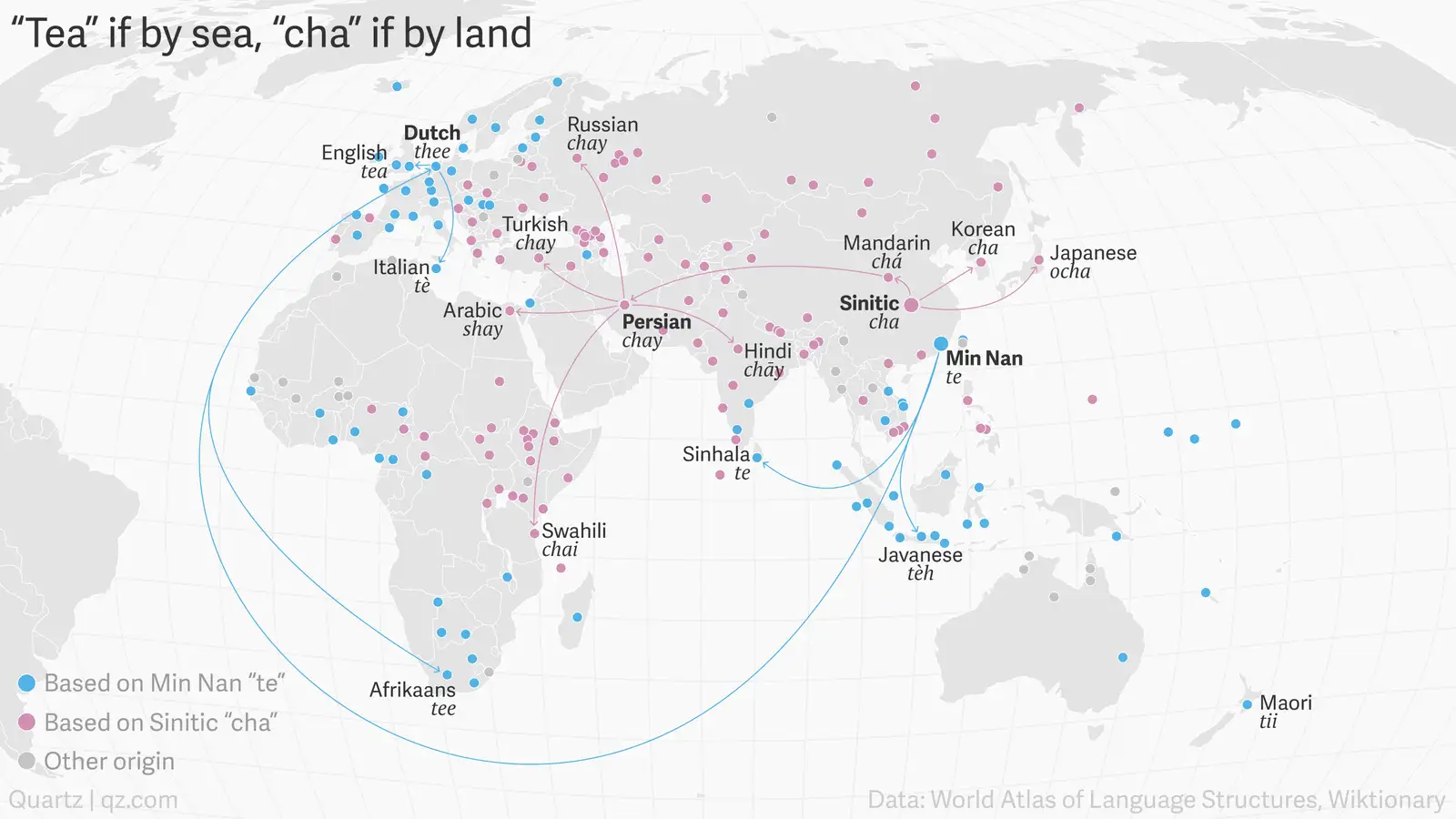

My favorite example of this is about tea, and why the world languages are split between describing the drink as a cha- word like “chai”, and describing the drink as a te- word like “tea”. Both words originate in China. Cha was the dominant pronunciation, but tē was the pronunciation in the southern Amoy dialect (or Xiamen Hokkien) which was the dialect spoken in some port cities, like Fujian.

Any languages which were initially introduced to the drink by trade routes originating over land, better known as the Silk Road, like Russian, Turkish, and Arabic, will each describe it with some pronunciation of “chai/shay”. Any languages which received the leaves via sea-faring trade routes, starting with the Dutch East India company, will use “te-“, like the tēh pronunciation of the Malay, the thee of the Dutch and the thé of the French.

It is one of the notable differences between Spanish and Portuguese, in where Spanish favors té and Portuguese, who traded through Macao, and not Fujian, prefers chá.

Modern Hebrew’s fascinating preference for תה (teh) reveals the German and English influence on the language, as opposed to the more obvious Arabic, Turkish, or Russian influences.

Quartz created a great map in 2018 which shows the relationship between the trade routes and the languages.

Orange Review

One reason I keep returning to the golden-colored citrus fruit is because it seemingly has a similar narrative. My theory has been that the language choice between the choosing some derivation of the word naranja and the word orange was related to the focus on the fruit’s fragrance as opposed to the fruit’s color.

As we saw a few weeks ago with tangerines and mandarins, there exist very dissimilar words with clear etymologies rooted in a “reddish-orange” color in Old Tupi and Chinese.

Greek

In Greek mythology, the idea of the golden apples (χρύσεα μῆλα - chrusea mela) of Hesperides, the object of Heracles’ (Hercules) eleventh labor, had already existed.

Latin

There are two synonyms in Latin for golden. The first is chryseus, which comes from the Greek for gold, but as I’ve mentioned before, was initially related to the idea of the mined precious metal, not the visual appearance.The second is aureus, which I’ve mentioned is a light-word.

From my own observations, medieval Latin also tended to use aureus as opposed to the chryseus, which was likely seen as too similar to the word christus.

Italian

In Italian texts, I’ve discovered spellings of both arancia and narancia, the first which is ostensibly from aurentium in Latin and the second which has a clear naranja influence. Regardless of which word an Italian speaker would use, the listener would easily understand that they were talking about an orange.

French

And yet, many scholars and internet websites are certain that the French pomme d’orange (d’or meaning gold) is borrowed from naranja.

German

Finally, I’ve taken the position that pomerantz comes from some conflation of pomme d’orange and mela arancia. But something felt a bit off about that. It did not sound like a direct borrowing from naranja either.

New Information, New Perspective

But what if I’m wrong, and everyone else is correct? How could that happen?

Thursday Night, 11PM

Late last night, I was doing some research for a completely different item which I thought would be today’s newsletter. I came across a Latin word in a 16th century Dutch text that explains the words for the “Araegie appele” in many languages.

- Greek - Chrysomelon (as above)

- Latin - Aureum malum (golden apples) and Malum hespericum (Apples of Hesperides), which some call - Nerantzium, which becomes Malum Anarantium and Arantium.

- German - Pomerantzen

- Dutch - Araengie Appelen

- French - Pome d’Orenges

- Spanish - Naranzas

I had never heard of Nerantzium before. I found an 18th century Cyclopaedia which explained:

NERANTZIUM, in Botany, a name given by some of the Greek writers to the citron tree. The ancient Greeks were not acquainted with the word, and it seems to have been formed in the barbarous ages from the word narange, the name by which the Arabian physicians called the same fruit.

It should be noted that it was only the barbarous ages if you lived in certain countries, it was in fact, a sparkling Golden Age if you lived in Iberian Peninsula.

There you have it. I was wrong. The rest of the world was right. It turns out that naranja was, in fact, the original word, and orange was simply an adaptation.

Even though there had been the idea of a golden apple for millennia.

5 AM Theory

Very early this morning, I awoke with a jolt.

What if I wasn’t completely wrong? And what if everyone else was missing a critical piece of information?

What if oranges are similar to tea?

We already know from a few weeks ago that Russia, which ostensibly was introduced to the citrus fruit from the Silk Road, called them Chinese apples. And Spain called them naranjas because they were introduced to them by the Arabic-speaking world.

ANTZ, ANTZ, ANTZ

I kept coming back to the “antz” in Nerantzium. The word seemed… familiar. It wasn't Greek or Latin, it reminded me of Hebrew.

So I considered an alternative theory: What if we don’t look at physical trade, but rather at intellectual intercourse?

Jewish Translators

How did the European languages learn the knowledge of the so-called “Arabian physicians”? It was translated by 12th century Andalusian Jews, like Samuel ibn Tibbon, whose father Judah emigrated from his native Spain to Provence, in the south of France, and translated works from Arabic to Hebrew.

We spoke about him in the newsletter about rainbows regarding his Hebrew translation of Ibn al-Batriq’s Arabic translation of Aristotle’s Meteora. He also translated Maimonides’ (noted rabbi, physician, and philosopher) Guide for the Perplexed from Judeo-Arabic (a dialect of Classical Arabic, written using the Hebrew alphabet) to Hebrew.

In his introduction to the Guide (paragraph 21), Maimonides quotes Proverbs 25:11, which also refers to “golden apples”, and in the Judeo-Arabic writes “תפאחהֵ ד’הב” tapuha dahab, or literally, “golden apple”. Obviously, this proves nothing, besides for the already established fact that people spoke about golden apples for millennia.

Fragrant Flowers

But I noted something odd: The Talmud (bBerakhot 43b) makes a distinction about making a blessing for smelling the fragrance of a narcissus flower. It receives one blessing if it is planted in a garden, and another if it is wild. The word in Babylonian Judeo-Aramaic is נרקום (narkom), obviously a Greek loanword, with the final letter being easily confused or swapped.

When Maimonides cites the same law in his Mishnah Torah (Berakhot 9:6), he refers to the flower as a נרגיס (nargis). In Arabic, the word is spelled similarly, with a ﺝ (jim), pronounced like a J, so narjis.

Even if the Greek shares a common ancestor with the Arabic for the flower, here are three different middle letter pronunciations: K, G, J. When you add in how narcissus is pronounced with a soft ⟨c⟩, you begin to see how easy it would be to assume.

Transliterations are hard

Similarly, elsewhere, I found that Greek loanword נרתיק (nartik) (case) is translated in 1640 dictionary to Narthecium (medicine box). In Greek, it would be ναρθήκιον (narthḗkion).

More importantly, in that entire dictionary, the only words with a “tz” were transliterations from Hebrew / Judeo-Aramaic, namely from the צ (tsade) in the Hebrew aleph-bet.

Therefore, the world Nerantzium likely underwent at least two different translations / transliterations, through Arabic and Hebrew, before the German or French speaker would adapt it to their language. And that was the only source they would have had for this word that could theoretically be Greek. And there would not have been vowels in Hebrew for the Latin, German, or French translator to use.

Borrowing and Lending Words

Sometimes people aren't sure if their language is borrowing or lending word, or both. Arabic medical books, like Avicenna / Ibn Sina’s 11th century Liber Canonis Medicinae (Canon of Medicine), borrowed terminology from the Greek, which meant that when they were translated to Hebrew and then Latin, and it was not always clear where the original word was from.

I had found an early 16th century Latin writer (1504) use the term narantiū to give a name for a citrus fruit. They were not likely going to assume that Nerantzium, which could theoretically be derived from Greek or Latin, was going to be the same thing. And they didn’t know Arabic. In fact, in a 1611 Spanish dictionary, they not only thought that νεράντζιομ (nerantziom) was the Greek name for oranges, and the Latin name was malangulum. I have absolutely no idea how that happened.

By Taste or By Book

Tasters

The people who would have initially encountered an orange in the Iberian peninsula would assign the name they were told by the people who provided it to them. Ironically, they incorrectly thought that the word they used was rooted in Greek.

Readers

The people who had only encountered golden apples in books, and had read of some unintelligible translation of a translation (of a translation) of a name that sounded Greek, decided to name the fruit in the spirit of the golden apples, with a nod to the “Greek” root. In essence, they named the golden apples before most people even encountered them.

Why does this matter at all?

Just like most of what I research, it doesn’t.

But, it's a matter of understanding intent. German, French, and Italian all chose to adapt their understanding of the Latin and Greek words to their language. Spanish adopted the name that was given to them.

Etymologies tell us about how people lived, thought, believed, and interacted with one another. It's easy to ignore the details about how the transmission occurred, but in this case, the Hebrew translator's decision to change a single consonant forced every other language to adapt the word to their alphabet.

The orange may be a simple, delicious fruit, but studying the etymology of its name tells the story of myth, adventure, persecution, translation, exploration, confusion, medicine, and more.

There is meaning in everything, if you care enough to look for it.