A Flower by Any Other Name Wouldn't Be As Golden

A follow-up to last week's newsletter about Vincent van Gogh and sunflowers.

While reading through Van Gogh’s letters for last week’s newsletter about Vincent van Gogh and his self-identification with sunflowers, I started down a bit of a rabbit hole about sunflower-related histories and etymologies. As I had noted in the newsletter, he had shifted from writing to Theo in Dutch to writing to Theo in French by the period in which he begins his sunflower-mania.

In this newsletter I'm going to:

- go through the words for sunflower in various languages

- share some late 16th century and early 17th century Flemish and Dutch art of sunflowers

- attempt to understand what van Gogh really meant about feeling like a sunflower

There is no single sunflower.

There isn’t a single flower species which one could point to describe what we call sunflowers. In 1951, Professor Charles Heiser published an article called "The Sunflower Among North American Indians" in which he wrote about the three dominant varieties of sunflower plants which were native to the Americas and transplanted to the European continent.

The common sunflower, Helianthus annuus L., comprises three varieties: H. annuus var. lenticularis (Dougl.) ., the "wild" sunflower; H. annuus var. annuus, the "weed" or "ruderal" sunflower; and H. annuus var. macrocarpus (D.C.)., the giant sunflower which is cultivated for its edible seeds.

Old New World

Sunflowers were part of Native American, Aztec and the Mayan cultures and cuisines. What we refer to as sunflowers are actually indigenous to the Americas, and were only “discovered” by European explorers in the 16th century.

Francisco Pizarro, the Spanish conquistador who encountered the Incas, and shared the myth of El Dorado in Peru, was the first European to discover the sunflower. The Incas, which we know worshipped a sun god, apparently used golden sunflowers in their worship of that god.

For example, in Aztec culture, the Nahuatl word for sunflower was “chimalxochitl” (shield-flower), because the tops of the sunflowers appeared similar the shapes of the Aztec warriors’ shields.

The Onondaga tribe which is in what is now considered New York, included sunflowers in their creation story. Heiser shared multiple names for sunflowers in their language, but other dictionaries I consulted did not seem to give any more context.

Why is a "sunflower" called a "sunflower"?

It seems fairly obvious why a sunflower is called a “sunflower”, it’s because it has yellow petals coming out of the center, which appear like the rays of the sun.

The word for sunflower for Dutch is zonnebloem, which can be translated literally as “sunflower”. Again, it’s the most obvious word for what a sunflower represents to us.

However, in French, the word is tournesol, literally, meaning “turning of the sun”. Similarly, the Italian “girasole” and Spanish “girasol” both meaning the “rotation of the sun”. This refers to how flowers rotate toward the sun, or heliotropism, when they are young. These come from the Ancient Greek - ἡλιοτρόπιον (hēliotrópion) and Latin - heliotropium , to describe a certain flower — heliotrope, which followed the sun.

Fun facts about Heliotropes

- the heliotrope is actually a light purple color.

- another name in Greek was σκορπῐ́ουρον (skorpíouron), a translation of which was found also in the post-biblical Hebrew עוקץ-עקרב - oketz akrav, meaning scorpion's bite, because the flower looked like a scorpion's bite.

The Jerusalem Artichoke

An eggcorn is a relatively recent linguistic classification for words which commonly misheard, to the point where the misheard word becomes used. For example, it makes sense for an acorn, which is shaped like an egg, to be called an “eggcorn”, if you had no context whatsoever.

The Jerusalem Artichoke has nothing to do with Jerusalem. It comes from a mishearing of girasole articiocco, which would literally be “sunflower artichoke”, or “sunchoke” as it’s also called. The flower at the top of the root is a sunflower.

(To make matters even more confusing, the French and German words for Jerusalem Artichoke are actually Topinambour / Topinambur, which itself is misunderstood, so it was derived from the Old Tupi name of the South American tribe which had discovered the root — Tupinamba, not a color word in the slightest. It doesn't have anything to do with amber, comtrary to the initial reading of the word.)

Sunflowers in Cyrllic

Some of the greatest producers of sunflowers on the European continent are Ukraine and Russia. Even between the two languages of Ukraine and Russia we see a distinction in how they call sunflowers:

- The Ukrainian соняшник (sonjašnyk) translates to a nominalization of the word “sunny”.

- The Russian Подсолнух (podsolnux) is more connected to the phrase “towards the sun”.

Earlier Sunflower Art

Anthony van Dyck, a Flemish Baroque artist from Antwerp, who in the early 1630s, as the court painter of Charles I in England, painted “Self-Portrait with a Sunflower” . The painting was connected by scholars to his allegiance to the royalists in the English Civil War (against the original black sheep).

However, scholars have attempted to connect this to the 16th century emblem books, which connect the sunflower to loyalty, because, as I mentioned above, the sunflower in French and Spanish tournesol or girasol turn to follow the sun, like a loyal subject. I'm not convinced.

If we look in a contemporaneous 1632 French / English dictionary, we see that the name of the flower was connected to gold:

- Herbe solaire. The Marigold

- Herbe au soleil. (au - towards the sun) very great, round, flat, and faire yellow flower, which turnes with the sunne, and ever looks towards it;

- Herbe du soleil. (du - of the sun) the marigold; also, Heliotropium, Turnesole, wartwort.

In van Dyck's painting, the sunflower seems to shine, just like his shiny gold chain, which conveys the interpretation of the sunflower being symbolic / emblematic of the sun. If we connect the “color war” between the factions between being the light and the dark, he obviously was choosing a side.

Other Flemish and Dutch Art

It makes sense for the Dutch to associate sunflowers with the golden color of the sun, because remember, the Dutch loved the concept of gold.

If we look at the earlier Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel who painted the sunflower between 1575 and 1580, he quoted Psalms:

- "In SOLE posuit Tabernaculum suum." ps:58. (“He has set his tabernacle in the sun.” Psalms 18:6) (Latin Vulgate Bible);

- "Fecit Lunam In tempora SOL cognovit occasum suum." ps: 103. (“The Lord has prepared his throne in the heavens; and his kingdom rules over all.” Psalms 103:19) (Latin Vulgate Bible)

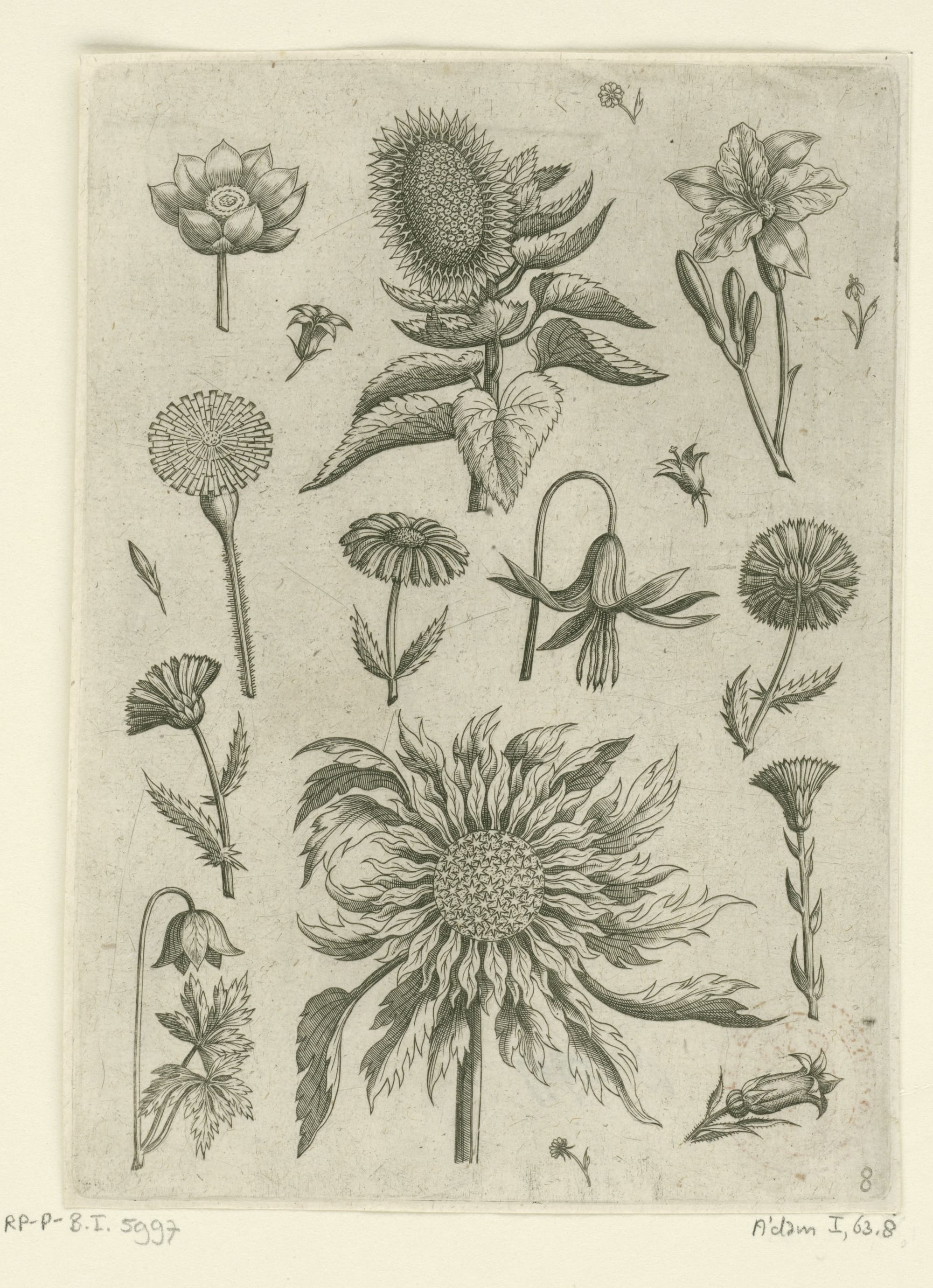

And other early Dutch artists like:

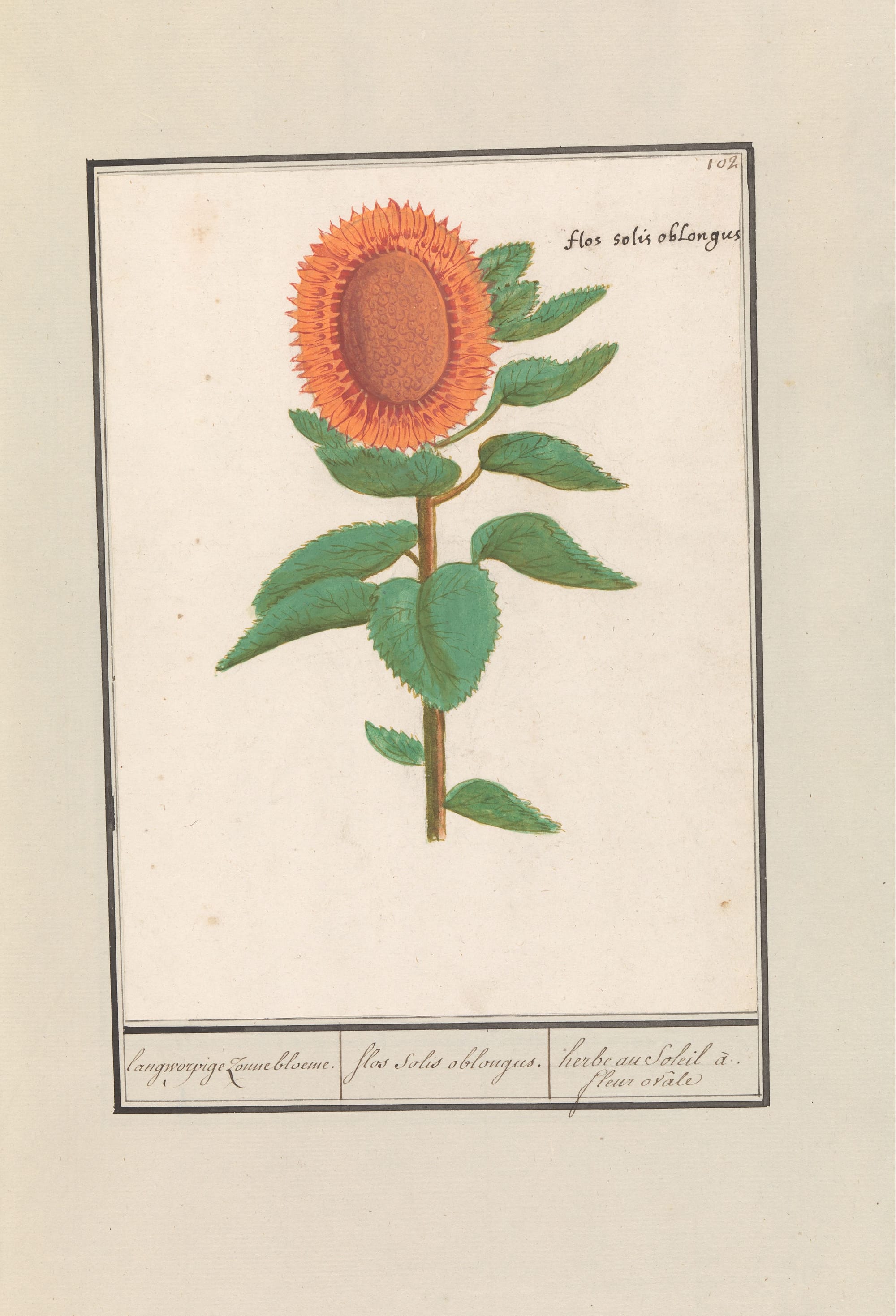

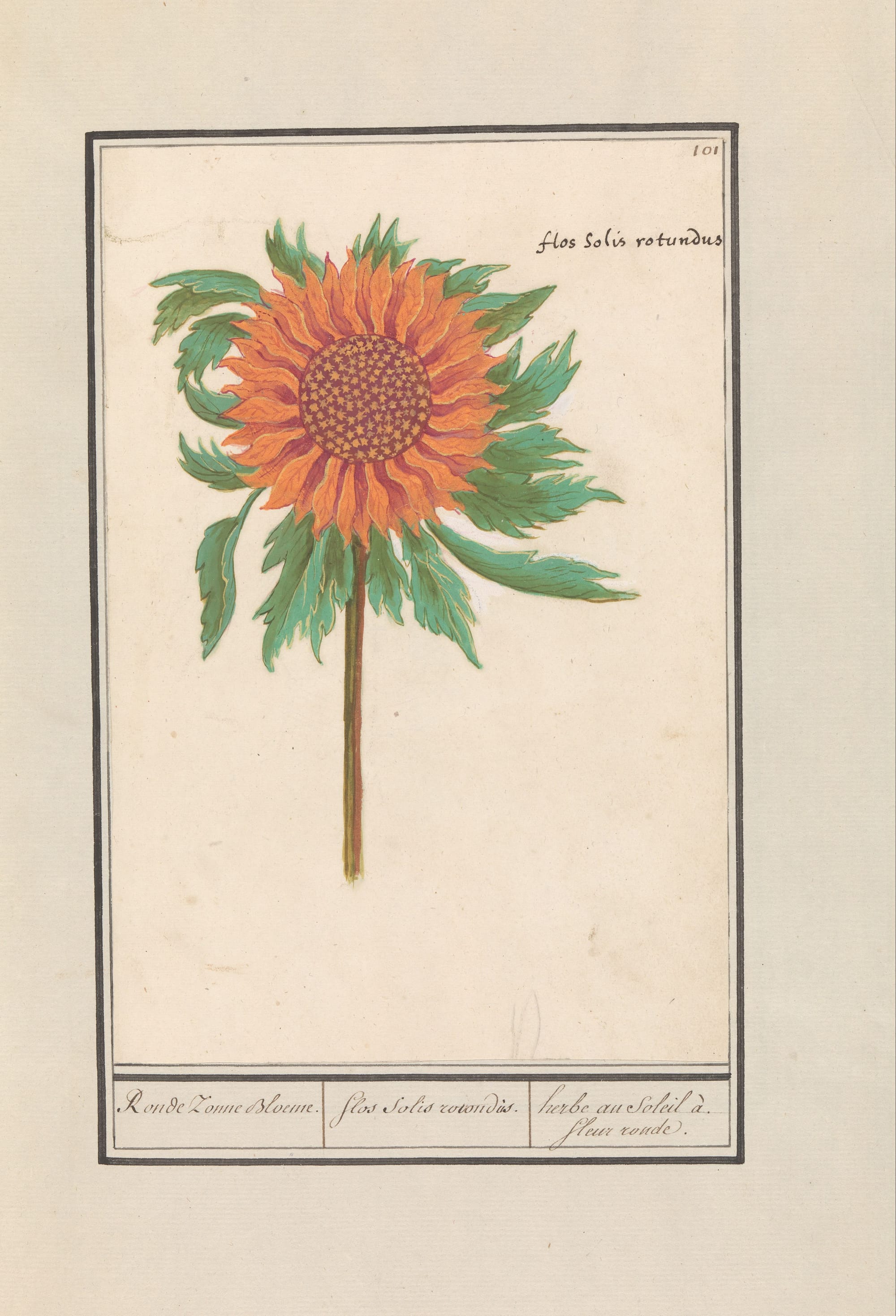

- Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt - who referred to it as Flos Solis / Zonne Bloeme (pre-1610)

- Adriaen Collaert - in a pre-1618 piece, Zonnebloem en andere bloemen (Sunflowers and other flowers).

Seemingly contrary to this, the Dutch poet and playwright Theodore Rodenburg referenced the sunflower (Zonne - Bloem) in his 1618 play Rodomont en Isabella, and how it followed the path of the sun. However, it seems that the play what an adaptation of an Italian (or perhaps Spanish) poem, which would have used the concept of the girasole, so it doesn't really tell us anything about the Dutch.

Back to van Gogh

Vincent wrote multiple times about how the stronger sun in Arles made the world brighter for him, and how artists from the north (where it was less sunny) should come south.

In van Gogh's letters, the shift from the Dutch to the French thinking makes a lot of sense when we contextualize the previously quoted letters.

He celebrates being connected to nature and finding the sun invigorating.

Here I’ll have more and more the existence of a Japanese painter, living close to nature like a petit bourgeois. So you can easily tell that it’s less gloomy than the decadents.

The bright sky empowered him.

To want to see another light, to believe that looking at nature under a brighter sky can give us a more accurate idea of the Japanese way of feeling and drawing. Wanting, finally, to see this stronger sun, because one feels that without knowing it one couldn’t understand the paintings of Delacroix from the point of view of execution, technique, and because one feels that the colours of the prism are veiled in mist in the north.

He felt like a tournesol, one who followed the sun and thrived in it, not like a Zonne bloem which shared the golden color of the sun.