This story is bananas. (Or "how banana became a color.")

In under a half century, the humble banana went from being an exotic fruit to an eponymous color. At its peak, the fervor for this fruit could only be compared to that of the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 1630s, albeit in a very different way.

In under a half century, the humble banana went from being an exotic fruit to an eponymous color. At its peak, the fervor for this fruit could only be compared to that of the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 1630s, albeit in a very different way.

During that time period, it was the star of the most popular song in the world, as well as the reason for a nearly 40 year collection of targeted wars by American multinational companies and the early American military industrial complex in Central America, some of South America, and the Caribbean. The “Banana Wars” resulted in the creation of what the American writer O. Henry coined the phrase “Banana Republic” in his 1904 collection of short stories “Of Cabbages and Kings”.

Millions lost their lives. Billions of bananas were eaten.

Banana (as a color, history)

To provide some context, in 1904, when the color was described in a British magazine, it was an interesting comparison.

The material is softest Liberty Myrana satin of the new " banana " colour, which is almost a faint apricot.

– Navy & Army, March, 1904

Comparing it to another fruit, feels a bit nondescriptive.

A decade later it was referred to in America as “banana” yellow, and by the next decade it was just “banana”. From it needing be explained, to having it as a hue of yellow to being something within itself is a great trajectory. Around 1928, there even was a color described as a "banana red". (I believe that it is the color orange.)

A leather goods trade journal in 1913 mentioned "banana" twice as a color in its dispatches from Paris one regarding inner linings for handbags, and the second a few months later regarding the color of a brooch in the center of a parasol cover.

An interesting innovation with respect to linings is to be noted. Hitherto linings to match the leather have obtained almost universally save for the inside division if furnished with a frame of its own for which white was generally adopted. Now some of the choicer productions are lined throughout in such light colors as pale beige or pink, banana or gold shades. A bag lined in this way gains much in elegance, the delicate hue of the interior making up for its outward simplicity.

–Trunks, Leather Goods and Umbrellas, Paris Letter dated 2/21/1913.

This subtle hidden pop of color is reminiscent of the red on the bottom of Christian Louboutin's shoes or of Edo-era Japan.

Frequently the broché is only used for the center of the parasol. For instance, half will be covered with violet or banana colored broché and the rest with a handsome band of filet or Venise over surah to match the center. Border trimmings predominate to an immense extent. Now it will be a wide border of black satin for a domed parasol covered for the rest with champagne colored taffeta rendered very elegant by the black portion being lined with deep cream lace.

–Trunks, Leather Goods and Umbrellas, Paris Letter dated 4/21/1913. (emphasis mine)

Reading the list of the other Parisian colors can make one's mouth water. Filet and Venise (as far as I can tell) are the colors of a filet of beef and venison (somewhere reddish-brown) and Syrah is a beautiful and delicious purple-reddish hue. This description of the color palette, together with the colors of "champagne" and "deep cream", convey luxury.

The same year, it was also reported that bananas and wine would be the two main luxury goods subject to an increased American import tax, resulting in millions of increased revenue.

The New York Times reported in October 1923:

The Fruits Seem to Have It

The fruit shades seem to have the call in the higher-priced hosiery for evening wear this season. One of the prominent makers of women's hose reports an active call for goods of a hue called banana, and indications are that it will continue to grow as the season advances.

– NYT, October 17, 1923

By 1927, the US newspaper, the Pathfinder reported:

Paris fashion experts have handed down their decree. So now the women of the world know just about how they should dress for Easter. Blue, they say, will dominate the gauntlet of colors for spring and summer wear. Besides all shades of blue, plaids will be prominent and all shades of white, banana, green, pink, rose, yellow, sand, red, brown and gray will be seen in profusion. Flesh pink, old rose, yellow, mauve, black, gold and silver will be the colors for evening wear.

Banana is listed, with no qualifications, alongside all the regular colors. ("Why sand?" is a question for another day.)

Veblen

American economist Thorstein Veblen in his book "The Theory of the Leisure Class" (1899) wrote about conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure. These Parisian parasols described in this dispatch seemed to meld the two concepts together.

Who sold bananas?

In the early years of the 20th century, bananas and peanuts were ubiquitously sold on every corner of New York by Italian immigrants. One politician estimated that a taxing the bananas would bring in millions in additional revenue.

A chasm was formed between the narrative of the immigrant street vendor and the reality of the banana businessman.

This preconceived led to a two-man play with an ethnic slur in the title "Donavo and the D––––" being put on in New York 1918. It also showed in a Supreme Court case in 1915 regarding a case of accidental manslaughter of a 42 year old father who was miscategorized as an immigrant banana seller when he was in fact American-born and worked for a fruit distribution company.

Industry magazines would look at at these upstarts as models for smart accounting. But that didn't stop those business people from being parodied. The banana merchants saw themselves themselves as a sort of entrepreneur, but were ultimately never taken seriously in society.

The New York Times relays a July 1923 account of a Spanish banana merchant in Paris who attended a reception given by Princess Eugène Murat. The story is three paragraphs long, and each paragraph is crazier than the previous one. Everything was going well until he enjoyed the port and cake a little too much and got into a fight with the butler, and the police removed him. He was swindled by an elegant American for 6,000 pesetas (nearly $50000 in today's money).

By 1927, financial math questions shared in newspapers included "How much did John and Frank each have to contribute towards a $1000 investment in a Cuban banana shipment which cleared 200% of the investment?"

There were get-rich-scheme ads for investments in banana plantations for only $5/month, which would result in $1500 annual profit (starting in the second year).

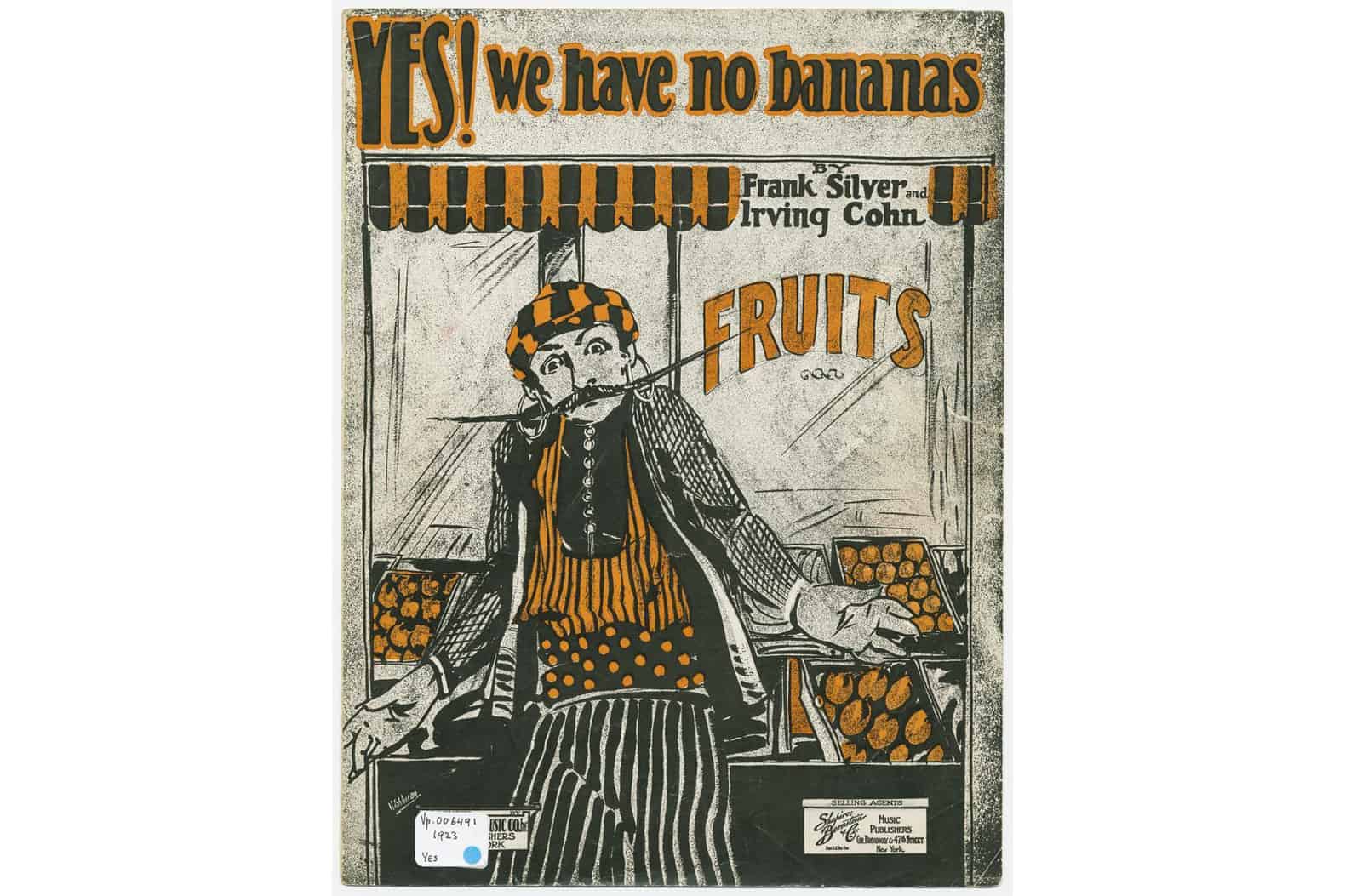

"Yes! We have no bananas."

One of the reasons for this shift, is a single song. In March 1923, during a banana shortage, a song was released that would forever change both music and advertising: “Yes, we have no bananas!” The songwriter credited the Greek proprietor of his regular store "Mr. Pete", who began every answer with the word "yes".

Who said that American music is inferior to that of other lands? No, it cannot be! We now have a weapon which repels at a single blow all the shafts aimed at us by malicious and prejudiced foreign critics. Of course we refer to the latest popular song hit–"YES! We Have No Bananas."

Let's observe its literary qualities:

YES! We have no bananas; we have no bananas today.

We just killed a pony.

So try our bologny;

It's flavored with oats and hay

We have those New Hamp-shyre squashes

They taste like go-Lah-shes

But YES! We have no bananas, we have no bananas today.

Could anything be more exquisite? Americans like it better than any song hit of recent years. They are playing and singing and whistling it by the tens of millions; copies are selling like hot cakes–over two million in four months. Only six months ago the artists who produced this gem were playing in an orchestra. They have now retired.

There have been bigger sellers, but the publishers of "YES! We Have No Bananas" predict that the new hit will eclipse them all. Anyhow, 97 per cent of the American nation is playing or singing it or dancing to its music.

However, Pathfinder readers will probably agree that of all the inane and idiotic songs "YES! We Have No Bananas." takes the cake. It has some of the silliest words ever heard in any song. Yet this very thing probably a counts for its success During the war the public was fed up on sentimental songs and in more recent years on "Mammy" and other Southern songs.

Then came "YES! We Have No Bananas." Here was something new something different. Even the crazy name was appealing. It wasn't a ballad or a c––– song, or a lullaby–it was just– different. And it sticks! Of course there are many imitation "Bananas" but the authors fall down on them. This song nearly "cornered" the music market.

–The Pathfinder, September 22, 1923

The song was released in Italy, Germany, and France, and that is just three of the versions I was able to find art for.

People were obsessed with the nonsense, and advertising journalists were confused as to what they could learn from this song. It was the sort of advertising that was seemed or was impossible to buy, and the first time advertising executives realized the power of songs.

Other companies would use that in their ads. "Yes, we have no bananas! but we have suits!" and similar pablum. In internet lingo, it was the first meme. It could explain the earlier New York Times report about people asking for hosiery in the banana hue.

This predated the famous 1926 Wheaties radio jingle, "have you tried Wheaties?", the first known case of using a jingle for advertising, by three years.

Bananas (split)

The banana split was created in either Latrobe, PA, or Wilmington, Ohio, during the oughts (around 1905) before becoming a delicious nationwide phenomenon. To gauge how big this became, we need to look at trade magazine for the Soda Fountain industry.

In February 1924, under the subject of "Where we get bananas":

The banana which in various forms is growing in popularity at the soda fountain illustrates the growing reliance of the United States upon the tropical world. A compilation made for the Trade Record of The National City Bank of New York shows that we have paid to our tropical neighbors in the Caribbean region nearly $400,000,000 for this single article of tropical food since our acquaintance with it began, forty years ago, and that we are now consuming more than 4 billion bananas every year.

-"The Soda Fountain", February 1924 (emphasis mine)

In the July 1924 issue:

"At our fountain and kitchen we have from 50 to 60 girls and 6 men. We catered to over 1,500,000 people last year. We have 300 ft. of fountain in the store and we are busy from 11 to 5:30 P. M. Some people think that in the 5 & 10c store soda fountains have poor quality food. But let me tell anyone that thinks thusly, that they are very much wrong, at least as far as the Kresge Company is concerned. We buy the best foods on the market, and our big leader is Chocolate Sundae at 10c and our Banana Split at 15c. In one day from 11 to 5:30 we sold 1,200 Banana Splits.

-"The Soda Fountain", July 1924 (emphasis mine)

While the bottom line is that they were selling 1200 banana splits a single day by 1924, helped make bananas popular, but did not cause the banana to become a color. It wasn't only the fact that it wasn't that the soda fountain was not considered a luxury. It was that once doesn't see the color yellow of the banana peels while eating their banana split.

Slang

Bananas entered the slang of the English language. They became ubiquitous to the point where I'm not sure if some usages were racist, bigoted, or innocuous. “Banana-oil” was a slang nonsense word (like baloney). Banana peel jokes were all over. One college town satire newspaper had four separate formulations of the same banal banana joke.

Conspicuous Consumption

Part of Veblen's theory had been to separate the "consumption" from the "production".

By 1926, far from being sold on street corners by Italian immigrants, bananas became one of the first fruits to be packaged and trademarked (what we would call "branding"). One way to describe it would be as a "Veblen good". Aspirational, but affordable luxury. The sort of thing you would request in the supermarket. The banana epitomized the concept of "conspicuous consumption" for a variety of reasons.

Short stories and plays would have characters randomly eating bananas, whether it added to the plot or not. And eating a banana in public has always made a statement.

There would even be banana-eating contests, leading one cartoonist to suggest "perhaps Darwin was Right."

In the accompanying 1927 article about the eating-competition fad,

Prof. Marcel Beutquen, noted French psychologist, sees another danger in this fad. Anyone who will risk discomfort of the kind that comes from over-indulgences, he thinks, is the victim of a complex. H e believes that in time by continued yielding to this obsession for personal acclaim, such a person will not only destroy his physical resistance, but impair his mental strength as well.

"The desire to occupy a place in the spotlight," he says,"is far more prevalent among persons of a low mental order than among normal human beings. Their ambitions are insipid, harmful and ridiculous."

Anthropological research of the era was certain to mention that in other cultures, the banana had a phallic association. It was even hypothesized that the banana was “the” fruit in the Garden of Eden, as the scientific names of bananas were "Musa paradisiaca" and "Musa sapientum".

Banana (as status symbol)

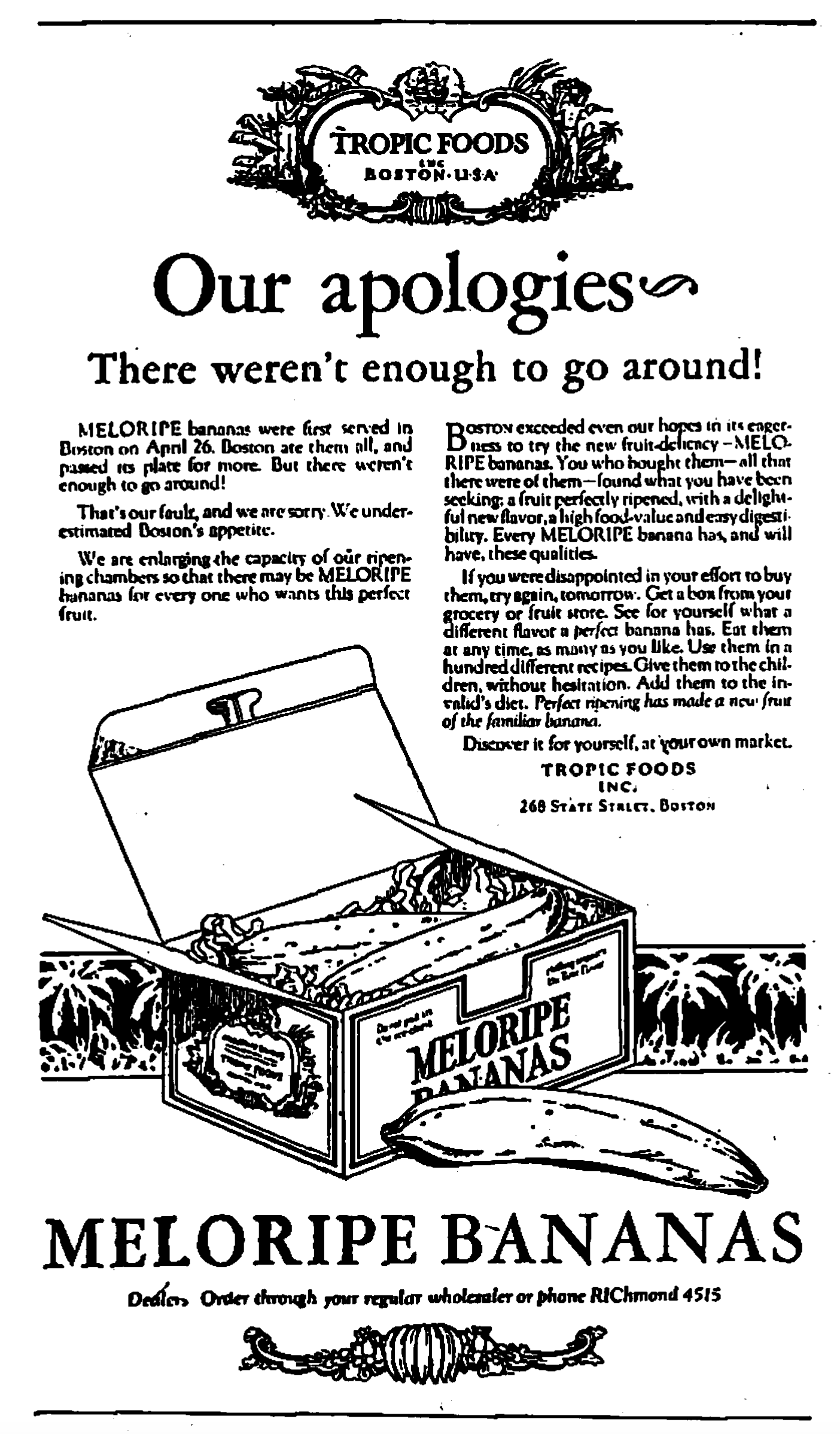

In 1926, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company, one of the companies responsible for the Banana Wars called “Tropic Foods”, released an advertisement about a lack of banana supply in Boston. “Our apologies ~ There weren’t enough going around.”

In addition to paying dictators and mercenary armies, the company began paying Madison Avenue. The advertisements educated the public to not keep their bananas in the fridge, refraining to do so caused bananas to ripen even faster and need to be consumed. The advertisements also highlighted how good bananas were for children and invalids.

Moreover, the packaging made the experience more standardized, with a better anticipation of what color people would be purchasing their bananas and at what color they should be eaten. It was no longer people hawking on the street, it was a top-down organization with logistics as its main concern. They had to ensure the temperature on the ships and in the railroad cars. It was not a simple feat. It can be compared to a 2000-era Starbucks, burning all their coffee beans to have a consistent color and taste no matter where you bought it.

(United Fruit Company rebranded in the 80s as Chiquita. Its main competitor Standard Fruit Company rebranded as Dole.)

"Meloripe" itself was a trademarked "scientific" process they created to ensure the perfect banana color at time of purchase. You were no longer just buying a banana, you were purchasing a status symbol of perfection.

And then the same year, banana was one of the hot fashion colors in the US. And for the next few years, it remained on various lists, with everything from shoes and gloves to sweaters to dresses and scarves. The next year there even was a “banana red” shade, which I’m not 100% percent sure what color that would be.

American anti-banana sentiment

One of the seemingly unwritten rules that whenever there is a fad, there are always people who are against it. Bananas were no different.

Besides the constant complaint to how little they were taxed, American fruit growers complained that it was still cheaper for companies to import, ship and sell bananas than their American fruit.

One Oklahoma reverend even explained how mosquitos were imported to London:

The generally accepted explanation was that they had come from America, like most evil things, in cargo of bananas! - Rev. T. B. Breckinridge, Okla.

Inconspicuous Production

Unfortunately the actual production of bananas was nowhere near the United States. That same year, 1926, an editorial for The Nation gave a sobering view of the American effect on the region:

There is something terrible as well as magnificent in the entrance of the new conquistadores of the tropics. Our attack upon humanity has been as ruthless and invincible as that upon nature. Native life in the tropics has commonly been poor and squalid but it has been warmly human. We have brought it medicine and sanitation for our own self-preservation and for economic reasons, but we have also brought it standardized ugliness and peonage. We have turned men and women from a fairly free and easy existence through desultory agriculture into wage slaves with sophisticated ambitions and vices. We have brought the drabness and soddenness of the mill town or the coal mine among the palm fronds of the Caribbean and the Pacific. In Hawaii we have even dispossessed the native Kanakas and imported the more industrious and economically profitable Japanese.

Probably the most serious of all the consequences of the introduction of the factory system to the tropics is the elimination of the small landowner and producer-the swallowing of his holdings by large plantations and his own downfall into a wage-worker and a renter. In Porto Rico individual farms decreased in number by about one third from 1910 to 1920; those of fewer than ten acres fell by one-half. The republic of Haiti, as a measure of self-protection, had a law against the alien ownership of land; the American Occupation, in the interest of industrial exploitation, repealed the measure.

– 8/29/1926 (emphasis mine)

The following month, The Nation ran a profile titled "Baron Banana in Puerto Barrios" about a "vainglorious" Guatemalan businessman named Don Francisco (Pancho) Beltran, introducing a different shade of yellow, "smallpox-yellow":

His courage and dignity and self-discipline never for a single moment would he slacken to the easy-going standards of the half-breed lands he despised yet exploited.

Puerto Barrios and its inhabitants accounted for his sentiments of superiority. Here are all the unmasked crudities of the feverish race of modern times to wrench forth raw materials. In Puerto Barrios Baron Banana rules supreme; and he rules rough-shod with little regard or the beauty or happiness of his people. Although to the initiated Baron Banana goes by the aristocratic cognomen of Musa sapientum, and President Orellana calls him Guatemala's Golden Prince, he is the most plebeian of the whole family of platanos. The Spanish, with satiric flair, have given him the phallic label "Fig of Adam." But abroad, in the United States, Baron Banana struts in fine attire. Fruit salads at banquets, banana splits in small town confectioners' shops, banana brandy for jaded Village flappers, dances to the tune of "Yes, we have no bananas", proclaim the importance that this single tropic fruit has acquired in the diet and imagination of the United States. Bananas, and more bananas! The United Fruit Company

and its lesser competitors can hardly keep pace. Their engineers go slashing through the jungles ; their railroads reach out iron fingers ; their smallpox-yellow clapboard buildings, hotels, bunkhouses, stores, offices, hospitals, warehouses spring up like monstrous fungi beside a hundred streams and marshes, in the heart of mangrove forests, and on a dozen lowering shores. The big green stems of fruit are cut from the trees, loaded on to mattresses in the open cars, and run down to a dozen ports, banana fronds dragging and rustling over the sleepers of the track.

Down to Puerto Barrios, which on the older maps is not even mentioned.

Puerto Barrios, boom banana port, epitomizes the haste and cruelty and bleeding rawness of the process. Back in the jungles the drive and jangle of the banana industry shrink in the face of vegetation so vast. The constant nerve-racking struggle to push back the monstrous tangled trees, to clear out the jungles with their reeking perfumes, poisonous insects, dangerous beasts, terrible fevers-this struggle is tragic yet puny in its relative inadequacy. But in Puerto Barrios the conglomerate ugliness of raw-product exploitation is spewed forth into the torrid sunlight. Here the smallpox-yellow buildings are not overshadowed by the jungle. They squat brazenly on the golden sands by the blue, brooding ocean.

– 9/15/1926 (emphasis mine)

Les Bananes en France

Those decades were a little different for France, though.

In short, in France, bananas became a Veblen Good decades before the United States. They were always tinged with colonialism and the obsession with how les sauvages lived.

In 1909, French artist Raoul Dufy, during his Cézanne period (before turning to Cubism in 1920), painted bananas. As far as I can tell, in more than 100 peintures de natures mortes (still life paintings) of fruit, Cézanne who died in 1906 never painted bananas.

There just wasn’t the same quantity of bananas available. In 1908, you could purchase extract de banane in a boutique, easier than you could buy a fresh banana in a shop. The color banane was more common, from sightings at the théâtre to designer clothes during the oughts. During the early part of the teens, commercial interests were trying to both perfect dying fabric a banane color and identify ways to use the banane cellulose to make fabric.

In the early 1920s, French soldiers returning from the war and the colonies would refer to one of their awards as les bananes, because it was yellow. This isn't to say that people did not make banana peel jokes, but it wasn't derogatory in the same way. The crêpe banane fabric was used all over the Parisian fashion scene.

One of the differences of the country was the perceived exclusivity of the French as opposed to the commonplace nature of the American banana. It was a triple issue: it had to be recognized enough, be considered exclusive enough for fashion, and it had to be appear luxurious and complimentary to its wearer.

Only in 1928 did French colonies Guadeloupe and Martinique shift from coffee and cacao (due to a cyclone) to growing bananas with a short growth cycle. From that point on, bananas became a lot more common in France.

(It should be pointed out that though Americans were aware of the French wearing the color before 1923, they still needed bananas to become important enough here before they could accept it as "luxury" color. There wasn't an automatic sense of "someone is wearing it in Paris" that caused it to be imported.)

Why do we wear the colors we wear?

But we don't really use "banana" as a metonym for a wearable color anymore.

It's partially because bananas have fallen from being a Veblen Good. They are just delicious, but they aren't more special in our diet than apples and oranges.

As we saw with the the Parisian parasols, clothing colors are usually associated with luxurious foods. Cream, not milk. Wine, not beer. Eggplant (aubergine), not carrot or sweet potato. Mustard, not ketchup.

Nearly a millenium earlier, orange (the fruit) created orange (the color). For numerous reasons, that caught on, partially because it filled a void between red and yellow. It is unclear how specific the shade of yellow (banana) is needed in non-fashion life.

Perhaps, the greatest proof that banana is not a color we need is that Curious George's friend in the eponymous series which premiered in 1941 is referred to as "The Man in the Yellow Hat", not "The Man in the Banana Hat". Even though Curious George initially made his acquaintance by mistaking the hat for bananas.

If anyone could have made banana a color, it would have been Curious George.