The True Meaning of Turkey

The Turkey (fowl) was named after the color of Turquoise (stone) whose name predated any connection to Türkiye (country).

Next week, families and friends around the United States will gather in centuries-old ritual commemorating a meal that had occurred a few centuries prior.

One of the central features of this feast is the chosen protein - the turkey.

Ignoring that the original meal probably did not include a turkey, which is an irrelevant fact, because things only have the meaning that we assign to them, and we have assigned a positive meaning of thanksgiving and gratitude.

The turkey is described as a “New World” fowl, one the first European refugees would have not been familiar with. However, if you look through most of the the dictionaries and etymological sources, the general consensus is that the turkey reminded them of fowl from back home.

If you will be celebrating this holiday, here is a quick fun fact that you can share with everyone else:

The name "turkey" most likely comes from the color turquoise, and not from any connection to the country Turkey.

Turkish Trade Theory

There is a prevalent theory that the bird was somehow called a turkey because of the English guineafowl trade with the country Turkey (now Türkiye, which I will use as a clear distinction for referring to the country, as opposed to the fowl or stone.).

The way some historians paint the picture is that the Western Europeans and the British were obsessed with Türkiye at that point, it being what fashionable and exotic at the same time, and named a series of seemingly unconnected items “turkey”, because they shared a same country of origin. These items include the aforementioned fowl, turkey-corn and turkey-wheat, and something called a Turkish stone.

I have a few slight problems with the narrative.

Similar to the case of the etymology of tangerine not being connected to Tangier, even though the words sound similar, it is a bit far-fetched for people to travel to a new world, see something that reminds them of something which was imported from somewhere else, and call it by the name of its importing country.

Is it possible? As they say, truth *is* stranger than fiction, but there are way too many holes in the story.

For instance, already in 1609, which is a dozen years before the year of the initial feast, we can find sources about a fowl referred to as “turkeis” in England.

If it was really from Turkey, why was there initially such a weird spelling?

Turquoise-colored Fowl

I would suggest that we have to remember how many birds are distinguished from one another, and that is by their color. We recently encountered that exact case with various species of teal (duck).

It is much more likely a scenario that the turkey-fowl’s coloring was “turkeis”, or what the French referred to as turquoise. Which makes a lot more logical sense why people would be able to spot a bird and give a name. Because at the end of the day, their understanding of species was pre-Linnaean (Meleagris gallopavo), and seeing a turquoise-colored fowl in the New World would receive the same name as a similarly colored cousin in the Old World.

In you peruse pictures of turkeys, you’ll notice different shades of turquoise in many of their heads or breasts. And it is not a surprise that no one make a big to-do about calling this fowl a “turkeis” because of its coloring, because to them the name was self-descriptive. If anything, associating the fowl with the name of a precious stone would have increased the fowl’s perceived value and beauty.

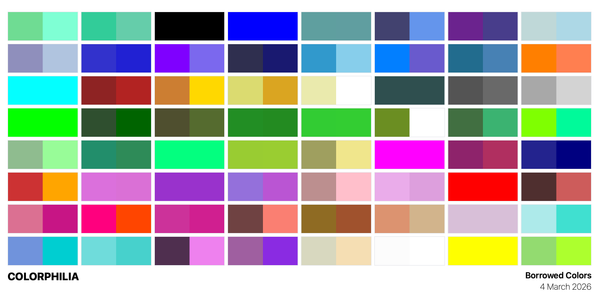

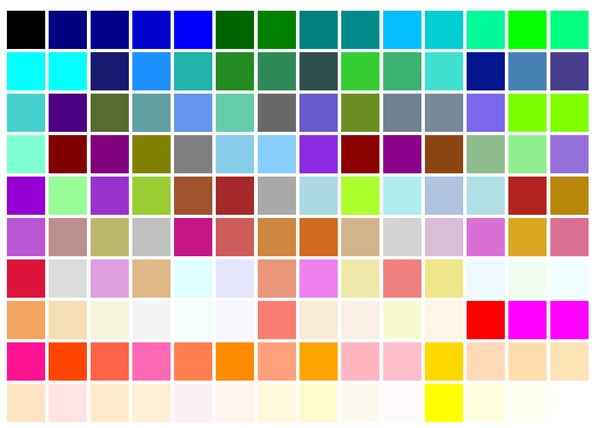

All Images from Wiki Media Commons

Turkeis (fowl) became turkey because we usually associate the s at the end of a word with the plural, and turkey-cock or turkey-hen is much simpler to say that turkeis-cock or turkeis-hen.

The Precious Stone

Color

Turquoise (the stone) has a color of anywhere between green and blue. The hue we most often associated with the color turquoise is exactly in the middle. But the Persians used the more blue versions, and the American southwest features more green versions of the same.

But obviously, the stone was named because of the country, right?

Right??

Right?!?

French

Turkeis was somehow related to the French Turquoise. The French spelling of Turkish would have been Turc. This addition of the “q” indicates a different substituted letter. It’s almost as if they took the name from somewhere else. (There are places, though, where they do use the word Turquois, without an ending "e", such as Arc Turquois, to mean "Turkish bow".)

Italian

The Italian family of languages is somewhat unique in that they referred to “sky blue” and “deep blue” as two completely different words. Sky blue is azzurro (or even celestre) and the deeper blue is turchino. This distinction is found in dictionaries as far back as the 1500s. And as we can see in a Tuscan / Castilian dictionary from 1587, the word turchino is translated as turquesado, or turquoise.

Stones of the Sky

We know that azzurro like the English azure, French azur, and Spanish azul originates in the Arabic and the old Persian words for the lapis lazuli, or the name of the “sky stone” which was used for the ultramarine blue pigment. Again, to remind you, ultramarine was from the Italian - oltremare – from across the sea.

This introduces the larger problem I have with associating turquoise with Türkiye.

We have two historically celebrated blue precious stones - the lapis lazuli and the turquoise - which both resemble the color of the sky. One is named after the sky, and the other is named after a relatively young country that doesn’t really have anything to do with the stone?

To take this a step further, to say that within a few centuries of the country’s naming, Italians began using that word as a color word to describe the color of the sea or sky is farfetched, to say the least.

A 1567 Latin dictionary translates iaspis aërizusa (literally “jasper that resembles air)” as Turckis (German), Turkoise (Dutch), Turquoise (French), Turchesa & turchina (Italian), and Turquesa (Spanish).

Addtionally Venetus, or Venetian Blue: is Turchino (Italian), Turcquine & Bleu (French), or Color de la mar (Spanish).

Short History of the Stone

The stone was found and used in Ancient Egypt, Persia, China, and the Americas. It was likely used in the breastplate of the Jewish High Priest.

Here is a paragraph about 16th-17th century Iran.

Shah 'Abbas I (r. 1587-1629) put the mining and trade of turquoise from the valuable old rock—all its output—under a royal monopoly.

This policy was in keeping with his mercantile tendencies and concerted efforts at establishing control over the empire, its resources, and its trade as a means of expanding the Safavid economy and its export revenues. The shah sought to stimulate the development of his mines, so much so that he reportedly ordered an unnamed European in his court "to inspect the mines all over Persia and see how they were being exploited."

He also issued ordinances restricting the export of raw and unset turquoise from the old mines, limiting work on the most valuable stones to Persian goldsmiths. Concerns that the old mines, of the finest turquoise, were becoming exhausted may also have spurred such careful measures to preserve these deposits for local craftsmen.

Shah 'Abbas himself reserved the premium stones of the old rock, to store in his treasury and to present as gifts to kings and princes. What the sovereign did not keep, he sold and traded away, and it was through this means that stones of the old rock reached the markets of Asia and Europe.

- Arash Khazeni - Sky Blue Stone 2014

Türkiye (a country named as such sometime between 900 and 1300 CE) was many things, but, Constantinople was more associated with gold.

Supposed trade routes aside, the one place not really associated with turquoise (the stone) is Türkiye. That isn’t to say that they didn’t use or trade in turquoise; they were in close enough proximity to the area of the world which was familiar with the stone.

In fact, in 1514, the Ottomans invaded and occupied Tabriz, Iran for a short time, and plundered the Shah's palace, looting his large supply of turquoise.

But if that was the date that Turkey came into the picture, it was centuries too late.

Judeo-Semitic Languages

The 13-14th century Spanish commentator, R. Bahya b. Asher described the stone in the High Priest's breastplate for the tribe of Naphtali was turquoise (טורקיז"א) and that it was connected to the tarkia (טרקיא) stone.

What makes it even more unbelievable is that there are Judeo-Aramaic sources, like the 3rd century biblical translation of Targum Onkeles, to a stone called tarkia (טרקיא) (Ex. 28:19), more than 500 years before Türkiye was ever named.

What is even more interesting is that tarkia had a connection to the sky.

By the time of the Babylonian Talmud, “tarkia” even had the meaning of a mirror, which is similar to how the ocean could be considered a mirror of the heavens.

In fact, the words “rakia”, and its relation to the sky and firmament, has roots in biblical Hebrew, from Genesis 1:6 to Psalms 19:2, Ezekiel (who compares it to the color of a sapphire or lapis lazuli) to Daniel 12:3. Job (37:18) even uses the form of tarkia.

(This association, by the way, isn’t solely my own, various medieval scholars and translators came made the same connection.)

And the word likely isn’t even Hebrew in its origins.

Assyrian

In the massive 26-volume 1977 Assyrian Dictionary of the University of Chicago, I discovered that tarku meant “dark-colored”. Not only that, tarlugallu means "rooster", as well as "a constellation or star", which is the origin for both the Hebrew (tarnagol) and Latin (gallus) words for rooster.

Additionally, in a different place in the dictionary I discovered a fascinating (if not sexist), quote:

i-ir-[q]í-a littagra šar inannama li-it-ta-(ar)-qí-a

my gossipy women are more numerous than the stars of heaven

Conclusion

There is a tendency to accidentally form an incorrect linguistic connection, and then to create a theory to back it up.

Whether or not there was a lively gunieafowl trade between Türkiye and England, it is much more likely that people were familiar with the color of the turquoise (stone) and named the turkey (fowl) based on that.

And regardless of whether the Ottoman Empire was ever a strong player in the turquoise (stone) industry, the name for the stone predated the existence of Türkiye (country), and was somehow connected to the sky.

How did Europe, en masse, choose the name turquoise for the stone? Especially as it was neither the Persian name, nor the Latin one.

I'm not quite sure, yet.