Every bride is beautiful.

Some wild theories about the color white.

There is a famous song sung at Jewish weddings which was taken from the Talmud (bKetubot 16b): “How does one dance in front of the bride?” The School of Shammai answers “as she is”, and the School of Hillel answers “as a beautiful and ḥasudah bride”. The discussion continues asking if it ok to lie about how beautiful the bride is. In the eyes of the School of Hillel, you should always look for and highlight one’s positive qualities. In other words, every bride is beautiful in their own way.

Does kindness exist?

Hasudah is usually translated as “kind”. People tend to connect the word with ḥesed which generally translated as “kindness”. Biblical translators use words everywhere from “mercy” to “piety” to “nobility”. Scholars have written, extensively, about our inability translate the word ḥesed in the bible.

The Septuagint creates a new word in Greek to translate ḥesed: χαρις (charis) ḥ-r-s. As you can probably imagine, this turns into the word “charity”. It doesn’t explain the original meaning, but its translators use about a dozen different words to translate ḥesed, so I’m fine with that. What makes this even more fascinating is that this word is feels related to the word κάθαρσις, or catharsis, coming from a root of καθαρός, katharos which sounds like a ḥ-s-r root. It has meanings of clear, clean, or pure.

Is anyone pious?

The word “hasid” is associated with pious people. There are many potential reasons how this evolved. I have theory that the word “hasid” is associated with the pious, because at a point pious people likely wore white. There is another Midrashic piece about the prohibition of cross-dressing. It explains it to be “for a woman to wear white clothing instead of colored clothing”. It seems like default to be pious, for a man at least, was originally to wear white.

When I was researching red tape, and came across the Talmudic source, which referred to two colors, translated by various translators as “red” and “white”, I noticed some fascinating etymologies for both. Red wasn’t really “red”, it was from the Aramaic for summaka or “sumac”, or sumac-colored, which is a reddish-yellow hue. The white was not from the normal L-B-N rooted word one would normally see, but a word ḥiwara (ḥivvara) which the Jastrow Dictionary informed me meant “white”, like white hair, white flour, and (white) leprosy. and was similar to the words for “dazzling appearances” and “cheap white wine”.

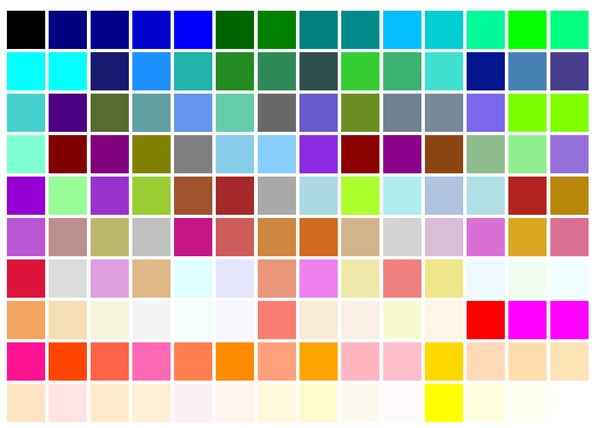

The light spectrum.

The root ḥ-w-r meant “to shine” and “to be white”, with literal and metaphorical usages like “to whiten” or “to cleanse” and “to make evident” or “to prove”. The latter metaphorical meaning is very similar to how we would use the word “to clarify” or “to make clear”.

In the Talmud (jChallah 2:1), it indicates that “nothing is clear (m-ḥ-w-r) except for the seven fluids.” The Mishnah (Makhshirin) lists them as “dew, water, wine, oil, blood, milk, and bee’s honey”. (Though, fruit juice, can sometimes be considered clear.) Regardless of the context of what this was referring to, it still shows that the root ḥ-w-r means either white or clear, but also, that clarity has does not necessarily have anything to do with color, but perhaps consistency or translucence.

The words for “clear” and “white” begin to be used interchangeably, because all “clear” indicates the presence of a lot of light. In some languages, like German, the same light words Schein, for gleam or shine, is a related to the words schön (beautiful) and Schnee (snow).

Light words are on a spectrum from transparent to opaque, which is how clear, clean, white, bright, or even hole or courtyard make sense to all be connected.

Coincidental whimsy.

On a whim, because I’m whimsical, I looked up the root ḥ-w-r in a Syriac dictionary. It included a lot of white and clear references, which is completely understandable, but at the very end, it included the word “stork”. This is weird and relevant because the word for the “stork” in Hebrew was “ḥasidah”, from the root ḥ-s-d.

More dancing.

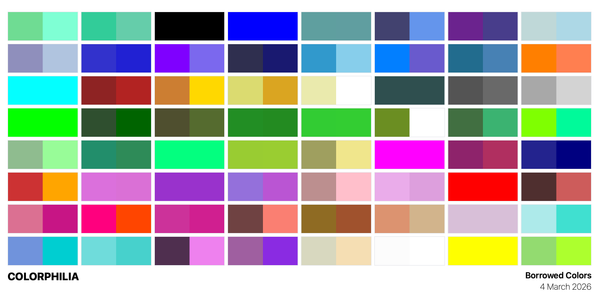

I was reminded of another Talmudic (bTaanit 26b) quote, about the joyous nature of the 15th of Ab (Tu B’av), which has been somewhat incorrectly described as the Jewish Valentine’s Day. All the single girls borrow white dresses and go out and dance in vineyards to attract a husband. They would make speeches of sorts, and highlight on their own good qualities, whether it was that she was beautiful, kind, wealthy, or came from a good family.

The discussion preceding the question of “how does one dance in front of the bride?” is one about a tradition where they would pass a barrel of wine in front of the bridge. One rabbi notes that you are supposed to pass a sealed barrel of wine in front of the bride if she is a virgin, and an open barrel of wine in front of her, if not. The talmud explains that the reason for this is so someone cannot lie on their marriage contract and get a higher dowry.

It is at that point that the debate about dance comes up. I believe that the phrase is from the School of Hillel actually means “as a beautiful bride and her bright white (dress)”. It is to explain that we treat every bride the same, regardless of whatever status she has.

A crazy theory that can't possibly be correct.

I’m obviously dancing around a very blatant question, which is exactly how are ḥ-w-r and ḥ-s-d related? We can see that in Aramaic (both Judean and Babylonian, to different extents) and Syriac, the words seem to be somewhat synonymous in meaning. However the w and s is pronounced, it seems a bit far-fetched to associate this with misunderstood accents or pronunciations.

Then I noticed that the Phoenician source for letter ḥeth in Hebrew is suggested to have come from the Egyptian hieroglyph for courtyard. The Egyptian pronunciation of the word courtyard was ḥ-w-d, and the Hebrew word is ḥ-ṣ-r. It doesn’t give an answer to why, but it does show that there is some relationship and interchangeability, for some reason between the s and w.

The Phoenician and Paleo-Hebrew waw (w) was 𐤅 and the Aramaic tsade (ṣ) was 𐡑 and because of boustrophedon, which was the practice of writing words both left-to-right and right-to-left on alternating lines, there were likely misreadings or typos of basic words, resulting in synonymous cognates with words that sounded nothing alike.

At the very least, it's a clear possibility.

Completely unrelated to all of this, Mazal Tov to my niece Yehudit on her engagement!