On the Color of Ancient Wine

This newsletter includes an intro to computer science, a quick explainer in vinification (winemaking), swine-ish sailors, biblical leprosy, the Passover Seder, bright-eyed goddesses, tithing, and raisin wine.

If you were to close your eyes and imagine the color of wine, you’d likely think of some shade of red or purple. Unless you are my mother, and then you may think of the bubbly Moscato d’Asti.

Therefore, in general, when we read the phrase “wine-colored”, we don’t usually think of any of the shades of a Chenin Blanc, a butter-colored Chardonnay, or a liquid gold Sancerre. We imagine a shade somewhere between a Merlot, a Burgundy and a Bordeaux.

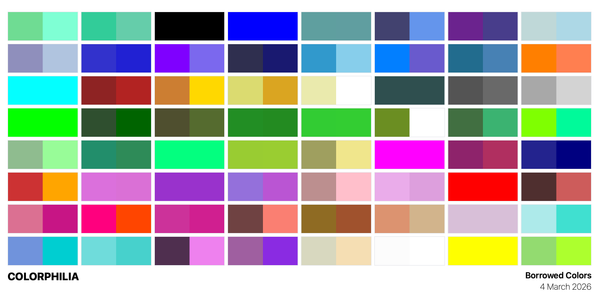

That's why the art I created is in those hues, because I created it before I fully researched this newsletter.

What I thought I'd be writing about

When I began to write this newsletter, it was with the intention of explaining etymology of the Spaniards referring to red wine as “tinto” (dark / tinted) and not “rojo” (red), and going down my favorite lesson of how everything was originally split into light and dark, with the concept of the generalized “red” wine being a much later development.

That’s not completely wrong, but it’s not completely correct.

My assumption was that all wines were initially split between light and dark, which turned into white and red. It’s not all that cut and dried.

How to Categorize Things

Wine can be categorized in different ways. If you were to go to any modern wine store, wine section in a supermarket, or wine list in a restaurant, you may notice a few different things. The wine may be sorted by country then region of manufacture, by varietal or blend, or color. A wine list may also then be sorted by fullness of body of the wine.

The three main colors generally used to taxonomize wine, at least in the modern era, are: white, rosé, and red. I use the word “taxonomize”, which comes from the Greek words meaning “method of arrangement”, purposely here.

The best way to arrange anything is to first identify the most common salient feature that may be similar or different, and to separate the items into one of those common features.

Quick Intro to Computer Science

By identifying high level common features, we are able to quickly categorize any wine by just asking "is it this (white) or this (red)?" You don't really need to know anything more than the color.

It reminds me of one of the faster computer sorting algorithms (on average) is a described as a “divide and conquer” algorithm called “quicksort” first conceived by Tony Hoare in 1959. As an example, let’s say we wanted to sort a list of numbers.

This algorithm would choose a number in the middle, and as it iterates through the list, the algorithm would decide if it was less than or greater than this number, creating two (unsorted) smaller lists of all the numbers comprising, respectively, less than the middle number and greater than the middle number. It would then repeat the process recursively until completely sorted, then rejoined.

It is a simple decision every time. Is it this (less than the number) or this (greater than the number)? It doesn't matter if there are 10 other numbers or a million other numbers, it does not become more complex.

If we had a list of 50 numbers, it would (on average) sort the list in slightly less than 84 moves, but in the worst case scenario, of a really mixed list, it could take as many as 2500 moves. That’s why it isn’t the best sorting algorithm, but it’s good enough for a basic explanation.

Biology 101

Biology uses a similar classification system with it first dividing into domain, then each domain into kingdom, then each kingdom into phylum, and so forth with class, order, family, genus, and finally species. At each level, there is something that everything in that group has in common, however much generalized and abstracted. This ensures that we are literally comparing apples with apples, instead of with elephants.

There is still diversity in each species, but we are able to repeat a specialized version of the same algorithm, for example, by color, or if we are talking about food, we could say by manufacturing process.

How to Make Wine

Historically, there have been many binaries (more or less) used to classify wine: sweet or dry, or young or aged, for two examples. Within each group, we can create more categories, like semi-sweet or semi-dry, a “vin de primeur” (aged only weeks before selling), aged 1 year or aged 20 years.

While we can include wines like port or champagne within these categorizations, we would most like separate them out into different categories before ever arriving to this stage, because a sweet extra sec champagne is different than a sweet port.

Modern Maceration

But just like champagne and port have different processes of production, so do the wines we would describe as “white”, “rosé”, or “red”. As raw grape juice (from the squeezed peeled grape fruit) in going to be more clear, maceration is used in order to leach the color, tannins, and flavor from the skins, seeds, and stems into the wine. This could be referred to also as “skin contact”.

Most white wine doesn’t have any maceration, or at the most, very limited. For example, Chardonnay doesn’t really gain anything from maceration, but more aromatic white grape varietals like Chenin Blanc or Sauvignon Blanc have limited maceration. White wines grapes with a normal maceration process produce something described as an orange wine.

Rosé uses red wine grapes with a shorter maceration process than would be done with red wine. And even within red wine, the Beaujolais Nouveau (a vin primeur), undergoes a relatively short maceration, as opposed to a full-bodied Cabernet Sauvignon.

I’m writing in generalities, as every single modern vintner may choose to increase or decrease maceration on any grape in order to create a different wine. I guess that that is part of the fun.

Terroir

Terroir, or literally land or soil, is another thing that changes the taste of wine. Being grown in a colder or warmer climate could affect the same grape in incredible ways. I remember a certain desert-grown Merlot I once tasted that was extremely unique, and the New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc has a grapefruity flavor that you don’t really see anywhere else.

In some countries there is an appellation or designation system acting as signifier of the terroir and process. In France, it’s called an Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) and in Italian, a Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC).

That’s why it’s only Champagne if it’s from the Champagne region of France, otherwise it’s just sparkling wine. Unless it’s from Spain, then it’s Cava, but besides that, it’s just sparkling wine. Or an Espumante from Portugal, but otherwise sparkling wine. Oh, and if it’s from Italy, it could be an Asti or Prosecco, only if it’s from those regions. Otherwise it’s a spumante (Italian for “sparkling wine”).

Obviously, these examples are more than just the terroir, these also describe a unique process.

Wine in Antiquity

The Ancient Wine Trade

Historically, and by historically, I mean in ancient Greece, they described their wine solely by the location of origin. Like the modern day appellations, the wines from the same general location tended to use the same process of manufacture with the same grapes, resulting in a similar taste. (According to scholars, while the wines would be described with the names of cities, they would in fact be based on wines manufactured on those islands.)

There were well-known wines from Chalkidike, Lesbos, Mende (which may be part of Chalkidike), Chios, Thasos, Rhodes, and Kerkyra. There were obviously more regions which manufactured wine, but these seem to be the ones which were most exported and valued. Each region had its own taste.

What did the ancients drink?

The categories that wines would be described as were generally malthakos (mild or mellow), melichroos (honied, or wine prepared with honey), and austeros (dry). The wine colors were mostly described as leukos (white), golden, or kirros (yellow/tawny).

The consensus is that they were not too particular about the color of wine, as we are. Most was lighter, the general rule seemed to be that they didn’t use maceration, especially to the extent that we do.

Wine as Medicine

In Latin, there is a line in the 2nd century BCE Roman playwright’s Plautus’ Menaechmi, where a doctor asks the titular character “Album an atrum vinum potas?” or “do you drink white or dark wine?” It's been often mistranslated as "red wine."

One of the reasons for such a distinction it was considered that darker wines had more of a laxative effect, versus lighter wines which had a more antidiarrheal affect.

This continues throughout much of history. I’ve found 16th and 17th century French texts which similarly refer to the medical benefits of wine, beyond being a truth serum.

Homer's Wine-eyed Sea

One of the first cases where we have wine used as a color description is in the Greek poet Homer.

To quote a Wikipedia article:

Wine-dark sea is a traditional English translation of oînops póntos (οἶνοψ πόντος, from oînos (οἶνος, "wine") + óps (ὄψ, "eye; face"), a Homeric epithet. A literal translation is "wine-face sea" (wine-faced, wine-eyed). It is attested five times in the Iliad and twelve times in the Odyssey often to describe rough, stormy seas.

…

One of the first to observe Homer's description of colours was British statesman William Gladstone. In his 1858 book Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, Gladstone analysed all aspects of Homer's mythical world, to discover a total absence of blue from the poet's descriptions of the Greek natural scenery. The word kyanós (κυανός), which in later stages of Greek meant blue, does make a limited appearance, but in Homer it almost certainly meant "dark", as it was used to describe the eyebrows of Zeus. Gladstone proposed that the Homeric usage of colour-terms focused not on hue, as contemporary usage does, but was instead primarily referring to how light or dark the object being described was.

A couple of first points: Homer doesn’t use the word “dark”. That's a bit of a mistranslation.

One of the suggestions is going back to the whole light to dark spectrum. If we go back to the light as completely translucent to dark as completely opaque, wine would be somewhere in between, regardless of the color of the wine. It's a nice thought, and an easy explanation.

However, in my opinion, people are being a bit too literal and it is clouding what Homer actually meant.

Sea Water Wine

Additionally, another taxonomy that they used in antiquity was mixed (meaning diluted with water, not blended with other wine) or unmixed. People would use sea water to dilute the wine, with wine from Lesbos even being described as having the taste of sea water without the need for dilution.

The Talmud

While it’s centuries later, the Talmud has a discussion about how the amount of dilution affects the required amount of wine to drink at the Passover Seder, a meal patterned after Greco-Roman Symposium. It would obviously not forbid diluted (or mixed) wine, as that was a common method of drinking wine. Additionally, one could either use new or aged wine.

The visual aspect of wine was not debated nor discussed, save for one line.

However, according to Rabbi Judah, it had to still have the taste and appearance of wine, calculating that it had to be a quarter measurement of wine. Another sage, Rava, explains with a prooftext from Proverbs 23:31, “Don’t look at wine…” with the understanding that wine must visually appear like wine, not just contain wine or even taste wine-like.

A Bloodless Exodus

One proof that the wine isn't red is that the Talmud doesn’t mention a much more likely association for why the diluted wine still must look like wine: namely it related to the blood in the Exodus story. But it doesn’t make that connection, because wine did not look like blood.

Centuries later, after the Haggadah was codified and red wine was common, red wine would become the drink of choice for the Passover Seder.

Which leads us to discuss the only time in the Bible that it seems to be referring to red wine, except that it isn’t.

The Proverbial Wine Eye

Note: I've edited most translations in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, just because I didn't particularly like the originals I found. They aren't perfect, I admit.

Proverbs 23

26: Give your mind to me, my son;

Let your eyes watch my ways.

27: A harlot is a deep pit;

A foreign woman is a narrow well.

28: She too lies in wait as if for prey,

Adding the unfaithful among men.

29: Who cries, “Woe!” who, “Alas!”;

Who has quarrels, who complaints;

Who has wounds without cause;

Who has dull eyes?

Note that in Genesis, in Jacob's blessings to his sons, Judah's eyes have the same description as Proverbs 23:29.

Genesis 49:12 [Judah's] eyes are duller than wine;

His teeth are whiter than milk.

30: Those whom wine keeps till the small hours,

Those who gather to drain the cups.

31: Do not look at that wine,

because it will cause you to become human

when you give your eye to the cup,

As it flows on smoothly;

32: In the end, it bites like a snake;

It spits like a basilisk.

33: Your eyes will see strange sights;

Your heart will speak distorted things.

34: You will be like one lying in bed on high seas,

Like one lying on top of the rigging.

35: “They struck me, but I felt no hurt;

They beat me, but I was unaware;

As often as I wake,

I go after it again.”

JPS (1985) incorrectly translates Proverbs 23:31 as “Do not ogle that red wine, as it lends its color to the cup, as it flows on smoothly.”

I chose to translate the problematic word "to become human" instead of "to redden", which could not grammatically be referring to the color of wine in any even. While the meaning could be "causes your eyes to become bloodshot", I think this is referring to the base animalistic nature man takes when over-imbibing. Becoming more human is not found on the path to wisdom.

The Septuagint translates it as "for if you cast your eyes upon the bottles and the glasses, then you shall walk more naked (γυμνότερος) than ever."

Proverbs 23:27 refers to a foreign or strange woman who in the following verse is laying in wait to treat men like prey.

I cannot but be reminded of the myth of Circe (who you may remember from her dealings with Glaucus) and when she gave cups of wine to the sailors, she turned them into swine. (Odyssey 10:230-240)

When Hermes was telling Odysseus how to save the sailors, he says in Odyssey 10:300 "lest when she has you left stripped bare (ἀπογυμνωθέντα), evil, and unmanly."

This all makes me reconsider Homer's phrase, which is also referring to the Wine-Eyed Sea. The first time he uses the phrase in Odyssey

1:181 And now have I put in here, as you see, with ship and crew, while sailing over the wine-eyed sea to men of strange speech...

And then at the end of Book 2,

2:393 Then again the goddess, bright-eyed Athena, took other counsel. She went her way to the house of divine Odysseus, and there began to shed sweet sleep upon the wooers and made them to wander in their drinking, and from their hands she cast the cups. But they rose to go to their rest throughout the city, and remained no long time seated, for sleep was falling upon their eyelids.

2:420 And bright-eyed Athena sent them a favorable wind, a strong-blowing West wind that sang over the wine-eyed sea.

The wine-eyed sea is used to contrast Athena's bright eyes.

It could literally simply mean "dulled", "hazy" and "disordered", not because of the color of wine, but due to the lack of visual clarity or mental acuity that most people have after drinking a few bottles of wine.

Which connects back the dullness of the eyes in both Genesis and Proverbs.

We then find this contrast of brightness and dullness with connection to wine again, in an unlikely location, while talking about biblical leprosy.

Biblical Leprosy

There is a Mishnaic (200-300 CE) tractate called “Negaim” (“Blemishes”) which discussed a biblical leprosy-type skin illness called “tza’arat” which is described in Leviticus 13, in which there is a depressed patch of white on the skin, where our understanding of the color of wine matters.

There are two signs of blemishes, which are actually four. The bright spot could either be like bright white like snow, and secondary to that is the spot looking like the lime in of the temple. The swelling section is as white of the shell of an egg, and secondary to that is the like the color of white wool, these are the words of Rabbi Meir. The Sages say the main swelling section is like color of white wool, and the secondary is like the white of the shell of an egg.

The precise blend of color of the snow is like wine mixed with snow, and the the precise blend of color of the lime is like blood mixed with milk, these are the words of Rabbi Ishmael. Rabbi Akiva says that the reddishness in either of these is like wine poured into water, only that the snow-like white color is bright and the lime-like white color is duller.

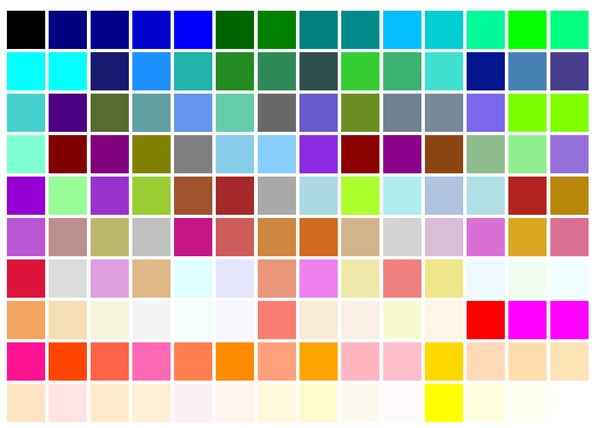

What we colloquially refer to “color” is comprised of three different aspects: hue, value, and chroma. Hue is basically the actual color of the pigment. The value (or the tone) is how light or dark a color is. And the chroma is the measure of the intensity from a pure bright color to a diluted thinned dull version of the same color.

Rabbi Akiva is saying that the hue is identical, but the chroma changes.

Shades of White

That said, the goal of the Mishna is to describe the exact shade of white Leviticus 13:4 is referring to when it says white. Snow, limestone, eggshell, and white wool are all different shades of white. Which makes this an interesting case, because I cannot imagine how many modern people have obsessed between painting a room snow-white or eggshell, and how they were this attuned to the variation of the shades nearly 2000 years ago.

As the target color was “white”, it seems like Rabbi Ishmael’s snow-wine mixture was white wine, which would dirty the snow a little but not too much. The imagery of blood mixed with milk results in a slightly pinkish hue, not red. Perhaps, somewhat of a flesh tone.

We see from both Jewish and Greco-Roman sources that contemporary forms of maceration were not done for most wines, but that there were methods that did extract the color from the grapes.

It just wasn't the best or the most mainstream of wine.

Tithing Grape Shells

In another tractate of the Mishna Maas. Sh. I, 3 regarding tithing for the Levites, there is something described as tamad (grape shells), which are then fermented in water, which provides a lower grade wine or vinegar. There, the distinction is if it was before or after fermentation.

We see in other Mishnaot that the distinction of “pre-fermentation” or “post-fermentation” is that of if this is considered raw natural material, or a post-processed material.

One could extend the logic and say that if maceration were a normal process in the wine-making process during that time period, then the grape shells would have already undergone a form of fermentation, and would be considered post-processed material.

Based on what we know about what actually gives wine the color were the grape shells, it is more than likely that their wine didn’t approach the red color we take for granted today.

Rereading Plautus’ question about “white wine versus dark wine”: when white wine was considered a superior drink, to the point of being compared to Aphrodites’ milk, and dark wine was made with the leftover grape peels, and more useful when a laxative is required, it would not be something something you would be proud to drink or serve, and it would be an awkward question that only a doctor would ask.

Sweet Sweet Raisin Wine

In the writings of the 1st century Greek physician and pharmacologist Pedanius Dioscorides, we learn about something called “raisin” wine, which is sweet wine made from sun-dried grapes (or dried on the vine and pressed), and which has multiple shades from dark to light.

Living around the same time, Pliny describes a different version of raisin wine called “passum” from making raisins out of white grapes, picking the berries and then soaking them in fine wine, and then pressing them. It’s not our modern version of maceration, but it created a thick sweet super alcoholic drink.

The Color of Wine in Antiquity Was White

This is all to make the point that even if they had examples of "red" wine during antiquity, it was an aberration, not the norm. Therefore, any random reference to the color of wine in antiquity would not be red, or even dark.

Even then, too much wine would give you blurry vision and perhaps even bloodshot eyes.

The Color of Modern Wine

We don't actually care about the general color of wine.

That said, while wine color is theoretically helpful it categorizing wine lists, it's not actually useful, even today. Merlot is merlot-colored, Burgundy is burgundy-colored, Rosé is rosé-colored.

One is more likely to purchase a wine based on its place of origin, varietal(s), description, tasting notes, or even the label on the bottle, more than by color.

Saying that something is a "red wine" is a shortcut for saying that it underwent maceration, is likely bolder, and probably contains tannins. The more richer the color, the longer the maceration.

We obviously care about the color of the wine in our glass, as one of many factors an oenophile takes into consideration while drinking a glass of wine, but "red" would not be the description one would use.

The past few weeks have been a bit hectic as I have been creating a new collection called "Ellipses (...)" which is now partially on display at GL Home Décor in Andersonville, Chicago. The pieces will be changing every few weeks.

If you are in Chicago during the next three months, please check it out!