Translating Biblical Colors

As a general rule of thumb, color is always mistranslated in the Bible. It’s not as much that they didn’t have the same colors that we do, it’s more that our concept of color is muddled.

As a general rule of thumb, color is always mistranslated in the Bible. It’s not as much that they didn’t have the same colors that we do, it’s more that our concept of color is muddled.

Exodus 28:4-6 writes about the creation of the priestly vestments for Aaron and his sons. I’ve compared ten translations of 28:5, Jewish in English and French and Christian in English, Latin and Greek, highlighting the color words and translating when necessary. There is no real difference based on religion, but I didn’t want people to assume that I was picking and choosing. You’ll see that there is confusion not only about the actual colors, but about what form the color is in. Are these already dyed yarns or wools, or are these the dyes themselves? Also, what are these colors all about?

“And they, they shall take the gold and the indigo and the purple and the crimson and the linen.” - Robert Alter, Norton, 2019

“they, therefore, shall receive the gold, the blue, purple, and crimson yarns, and the fine linen.” - JPS, 1985

“And they shall take the gold, and the blue, and the purple, and the scarlet, and the fine linen.” - JPS, 1917

“They shall take the gold, the greenish-blue wool, the dark red wool, the crimson wool, and the fine twined linen.” - Metsudah Publications, 2009

“Have them use gold, and blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and fine linen.” - NIV

“And they shall take gold, and blue, and purple, and scarlet, and fine linen.” - KJV

“Ils prendront de l’or (gold), de la laine (wool) bleue, de l’écarlate (scarlet) et du cramoisi (crimson), et du fin lin.” - Samuel Cahen, 1831

“Et ils emploieront l’or (gold), l’azur (sky-blue), la pourpre (purple), l’écarlate (scarlet) et le fin lin.” - Bible du Rabbinat 1899

“Accipientque aurum (gold), et hyacinthum (hyacinth) , et purpuram (Tyrian purple), coccumque bis tinctum (double-dyed kermes), et byssum.” - Biblia Sacra Vulgata

“καὶ αὐτοὶ λήμψονται τὸ χρυσίον (gold) καὶ τὴν ὑάκινθον (hyacinth) καὶ τὴν πορφύραν (Tyrian purple) καὶ τὸ κόκκινον (kermes) καὶ τὴν βύσσον” - Septuagint

My personal (initial) translation is:

“And they shall take the gold, the tekhelet, the argaman, the shani worm, and the linen.”

If you notice the translations, the modern ones tend to conflate hue with dye, the older ones do not. The Vulgate and the Septuagint both reference the dyes or dye-materials needed to create the ephod. Whether the Hyacinth is the dye referred to as tekhelet in the verse, is a completely different question.

Meaningful Colors of Luxury

There are historical sources of blue and purple dyes which became brighter with sunlight, namely the biologicals of the Murex rock snails. The Murex trunculus was used to create argaman more commonly known as Tyrian purple, named after the city Tyre in Lebanon. The Hexaplex trunculus was probably the snail from which they created the blue dye called tekhelet.

Additionally, there was a scarlet red dye called “Kermes” made from insects in the genus Kermes, specifically the Kermes vermilio species. We get two different color names for shades of red from these insects. From kermes, we get the color crimson. From vermilio, we get the color, vermillion. (The Vulgate mistranslates the “shani” as bis (twice), where in fact the “shani” is the type of insect.)

It wasn't just the dyes, even blue, purple, and red pigments were very rare and expensive, and had to be imported. The lapis lazuli stone was used to create blue pigment, the porphyr stone was used to create purple pigment, and cinnabar was used to create red pigment.

That is not to say that the three shared the same meaning.

Tyrian purple was so associated with royalty, there was a word porphyrogenitus, "born in the purple”. The Greek generals wore a ceremonial toga picta, a toga of solid Tyrian purple with gold thread edging.

The tekhelet was associated with religion and belief in God.

The red could denote all the metaphors associated with blood and victory.

This association with royalty and grandeur makes sense because Exodus 28:2 includes the direction that the sacral vestments should be for “glory” and “splendor” (Alter’s translation). It really didn’t matter what the colors were, as long as they were very expensive.

Joseph

With this understanding, we can also reconsider the statement Joseph’s כתונת פסים / amazing technicolor dreamcoat (literally "striped coat"). Every additional application of color added to the cost and value of the coat. So a garment manually dyed line-by-line in more than a single color was a status symbol. One couldn’t just dunk it a single time in dye. It took time and experience, and most of all money.

It was that same amazing technicolor dreamcoat that Joseph's brothers dipped into blood in order to fool their father that he had died (instead of being sold).

Symbolic Blood

Putting aside the statement of wealth and grandeur a vestment of these expensive dyes would make, they are all non-plant dyes, a fact that the Septuagint and the Vulgate mistranslated. While we in the 21st century may nitpick and say that the dyes are not actually the blood of the snails and the insects, the ancient world would not have same distinction.

I do not believe that it is too far of a stretch to connect the concept of Joseph's striped garment dipped in blood to this blood-striped ephod, especially as it was connected to the breastplate which featured colored stones representing the tribes.

Indigo and Counterfeit Tekhelet

Regarding Robert Alter’s translation, blue dye was historically very expensive as well, because there were few naturally blue organic materials that made good dyes. In Europe, they had a plant called woad (or glastum), which was also called pastel, which was not very good and quite expensive. The better blue dye came from the indigo plant, which entered Greek and Latin culture in small quantities from southeast Asia. It was called indico, as in Indian (from India), but the Portuguese changed it to indigo, and that’s the word that spread.

It is assumed that the קלא אילן kala ilan (the kala tree) of the Talmud (6th century, Babylonia, modern day Iraq) was referring to indigo. In Tractate Bava Metzia 61b, it states that someone wearing a tzitzit-fringe dyed with this indigo instead of actual tekhelet, even though they are identical in color, is ethically wrong and will be punished by God.

In other words, according to the Talmud, the color hue didn’t matter, the color dye did, and that was precisely what the modern translations got wrong.

Tautological Color

The color of gold is gold. The color of the hyacinth flower is hyacinth, anything else is just a rough estimation. The color of tekhelet dye is tekhelet. The color of argaman dye is argaman. The color of the shani dye is shani.

If there would have been a particularly dark or light batch of one of the dyes, it wouldn’t have mattered because it wasn’t about the precise color, it was about what the color represented.

The exception that proves the rule

As a coda, Robert Alter was probably the most correct of all the translations regarding what the color hue actually was. Tekhelet was indigo-colored, but it wasn't indigo. Argaman was purple-colored. Shani was crimson-colored. In fact, because the word crimson came from the bug in question, it was very correct.

He further explains the dye-making processes and their importance in the eastern part of the Mediterranean in a footnote on Exodus 25:4.

He concludes by mentioning:

“It is hard to imagine that these precious dyes would have been accessible to the Hebrews in the wilderness — this is one of several indications that the picture of the Tabernacle is in many ways an ideal projection rather than a strictly historical account.”

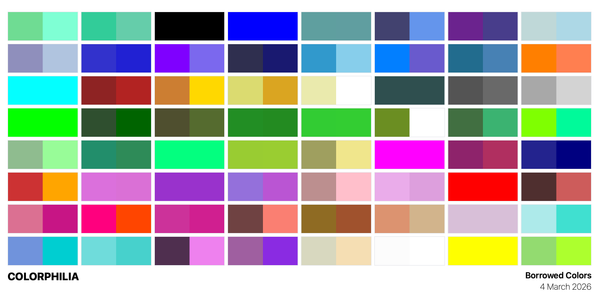

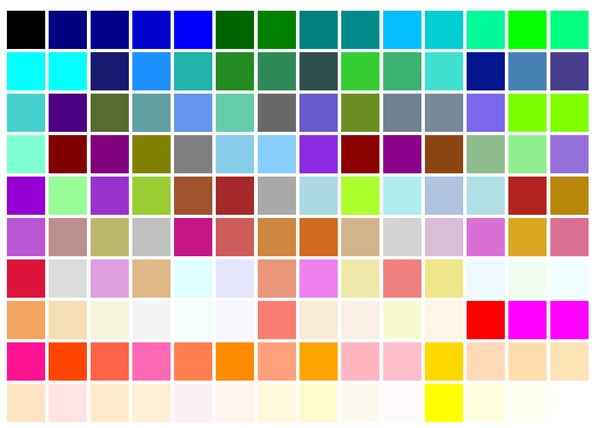

About the art

As we cannot know what each colors looked like, for each paperboard collage, I included multiple shades of each of the colors.