Drawing with Light

A few Greek and Latin phrases about drawing with light.

This week’s newsletter includes a correction to a flippant line I wrote last week, and a possible explanation to why we “draw” pictures, which is probably completely incorrect and will necessitate a retraction next week.

- The correction begins more than two centuries before “photography” (writing with light) was imagined, with the naming of the telescope, and explores a bit of the world and structure of the Scientific Revolution. It shows how the word “photography” was already a forgone conclusion by the end of the 17th century, even if it had never been written.

- English uses two seemingly synonymous and interchangeable words, “illumination” and “illustration” is the same way, when referring to the act of decorating manuscripts or books. A quick elucidation of their respective etymologies will leave you somewhat enlightened. As you can probably see from my dim attempt at a pun, the meaning of these words seems to connote a sense of “drawing with light”.

Mea Culpa

I made a mistake in last week’s newsletter about photography.

Well, a few mistakes.

First, I wrote the incorrect date on Walter Benjamin’s essay. It’s been corrected on the web, but in my haste, I erred.

The second, more grievous, error, was writing when I was trying to ascertain the earliest usage of the concept of “photography”. I wrote:

Earliest “Photographic” Usage

I always try to figure out what the earliest use I can find of a phrase. Curiosity is part of the reason, and the disbelief that people in 4 countries would magically begin using a phrase to mean exactly the same thing.

It felt flippant, and is not completely accurate, and I apologize. I quoted the Daguerre’s translator:

[Daguerréotype] is the name given to the apparatus fitted up on the principles of M. Daguerre’s system of photographic or photogenic painting. All scientific terms ought to express either a fact or a name. The French generally prefer the latter, English philosophers the former element of nomenclature.

In light of some additional research, this, too, is not completely accurate. And finally, I wrote:

It seems that the French used the term photographique and the English initially preferred photogenic. Photographic means “written by light”, whereas photogenic means “caused by light”.

That should have been my first clue that something that something much greater was at play.

It's all Greek to me.

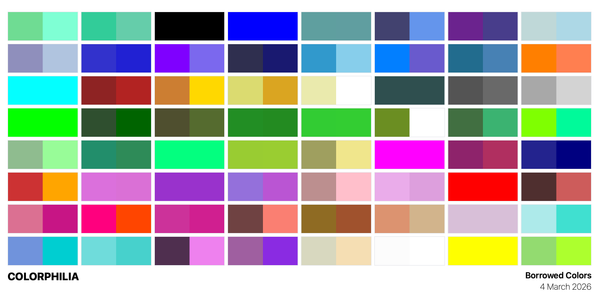

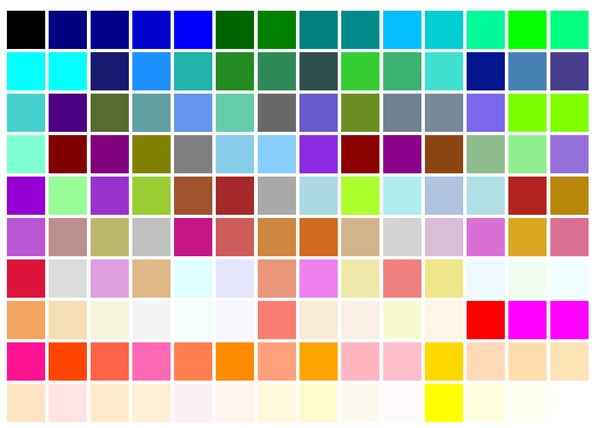

As these words were all from Greek, I thought about other modern inventions which were named in Greek: The telescope, microscope, barometer, hygrometer, thermometer, aerometer, anemometer, telegraph, phone (short for telephone), stereo (short for stereophonic), automatic, horoscope, arithmometer, semaphore, and odometer. Then I considered later mixed language words like fax (short for telefacsimile), television, and colorphilia.

This sort of nomenclature has been described as New Latin or Neo-Latin, but there is something much deeper going on here. I don’t think that this has anything, per se, to do with Latin, besides for it being a revival of the borrowing of Greek into Latin script, which could be understood by anyone all over.

The language of science and mathematics was Greek and Arabic, partially because they were continuing the conversations and debates started by Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Euclid, and continued by Averroes (Ibn Rushd) and Avicenna (Ibn Sina). Algebra was introduced to Europe in the 16th century through translations of al-Khwarizmi's 9th century work Al-Jabr. Geometry entered with the translation and publishing of Euclid’s Elementa Geometriae in 1533, and advances in optics happened after Euclid’s Optica was published in 1557.

When Europeans began studying Euclid, and learning both geometry and physics, they began to develop the scientific method, and start scientific academies, journals, and engage with other scientists and inventors all over Europe. Two of the earliest academies were in Italy and England.

While the invention of the telescope is mired in controversy, it is generally accepted that the word telescope was chosen by the founder of the Accademia dei Lincei, Frederico Cesi. One narrative is that by Greek mathematician and Academy member Giovanni (Johannes) Demisiani had provided the words for tele (far) and skopein (to see). When the microscope was invented there a decade later, they used the same nomenclature, with micro being the Greek word for small.

Decades later, English Royal Society member Robert Hooke published Micrographia, a book of pictures he drew through a microscope, fascinating the public with the possibilities of science.

The Name Game

Unlike many of the Greeks who had a theoretical bent, the scientific method was about observation and recording.

The Greeks also believed that there were four base elements: geo (earth), aero (air), hydro (water), and pyro (fire). As the new scientific method required careful measurement, anything instrument which would measure an element would be a -meter, from the Greek word to measure, metron. If the instrument would record something, it would be a -graph, from the Greek grapho, to write.

These names conveyed the scientific tradition they saw themselves as reviving. But these words had another, perhaps unintended consequence. Anyone who was trying to measure air pressure would call their device a “barometer”, for example. Such uniformity allowed people to compare and contrast. A “photometer” was the device for measuring light.

Suddenly, it was simple to name scientific instruments. Want to measure distance traveled? Use an odometer, from odos, for road. How about temperature? A thermometer, from thermos, for heat. One didn’t expect the odometer to measure pace or the thermometer to measure humidity.

Photo-graphy

So everyone who developed a thermometer or telescope know that they are trying to achieve the same thing. Whether your result is a cyanotype or a daguerreotype, you are still attempting photography, because this is the result of light-writing. Photometers, or light-measurers existed already, and even photosynthesis was discovered. It is most likely, to that end that understanding photosynthesis ultimately enabled photography, because it would be required to understand that light could cause a chemical reaction in a material, or that even that light heated up up more than shaded areas.

So it is very likely that if four people were all working on using light to create permanent images, they would have all referred to the process as “photographic”.

That said, the first usage I found of photographique was the one I mentioned last week, but it is completely understandable that any other inventor would have described the process in a similar way.

Drawing Light

What else would they have called it, anyways?

Latin offered two possibilities: illumination or illustration.

These words were used to describe drawings on manuscripts. At least at face value, the pictures metaphorically illuminate the text. But it’s more than just that. In a 16th century book I found on the “Art of Limming”, I discovered that “limming” was the art of “illuminating” manuscripts. A critical part of the process was the use of gold and silver, it was the art of introducing sparkling light into the manuscript.

So what’s the difference between the words?

If you track “illumination” and “illustration” back through Middle English and French, they return to Latin, and while they both have a connection with light, it has two wildly different paths.

IIllumination is connected to lumen, or light. The metaphorical take of knowledge being related to light preceded this by thousands of years, so it is no wonder that “illumination” could be understood in multiple different ways. Illuminated texts added both physical light and additional explanation to the manuscripts.

Illustration is derived from the Greco-Roman water purification ritual, Lustratio, which included a procession and often included sacrifices to Mars. It was sometimes performed for newborns and other times to purify and bless larger areas. Illustration is therefore connected to the connotation of white or clear, and clean, and therefore pure.

Which still doesn’t explain how something more known for cleanliness and purity becomes a synonym of illumination. Three possible explantions are:

- Illustrious is connected to having a distinguished reputation, or name. Lustratio was connected with a name-giving ceremony.

- It seems that it began to be used alongside the word "beauty" (or beautie), to connote "purity and beauty", which turned into honor, worthiness, or splendor.

- As it is based on a light word, the sun would illustrate, or lighten, the moon or the earth, with its rays. You may think of it as being washed over or baptized by rays of the sun. As I had mentioned in the newsletter On the Color of Ancient Wine, the opposite of bright (wise, intelligent) is dull (dark). By introducing light, one removes the dullness, and creates wisdom.

While the word "sketch" is connected with a more quick and spurious action, it is possibly connected to skia (shadow in Greek), which indicates making dark marks on paper. But illustration is about creating something which beautifies or brings additional light to the page.

Why we "draw"

We don’t say “drawing” paintings, we only use the verb “to draw” when it comes to whatever we describe as illustration. The word “draw” has been used with relation to water, like drawing a bath, in other languages.

After a little bit of research, I’ve identified two potential reasons why we use the verb “drawing” when we talk about creating illustrations:

- The functional answer is quite simple and straightforward: The process of illustration or illumination would entail initially taking a pencil or crayon which you would trace out all of the letters and pictures in the parchment, and then with a small pen or stylus “draw” all the ink you had poured into the indentations. So the object being drawn was the ink, not the picture.

- Part of the Lustratio ceremony was drawing water, so part of the illustration process is drawing with color.

Again, we see that the difference between the two words “illumination” and “illustration” comes down to a difference between if we referring to the result or to the process.

As we've shifted our publishing methods, and no longer use shiny materials to adorn pages, we’ve expanded the meaning of illustration to include all forms of depictions on pages of books, and we’ve left illumination in the field of actual light (or thought). In theoretical matters, we may say “elucidation”, meaning introducing light, which usually includes adding additional context.

Illustration has taken on a secondary meaning of situation which explains a point. (Like a spilled glass of red wine on a white shirt illustrates the reason why some people choose to serve white wine.)

Does any of this matter?

Much like many of the things I research, the exact date of the coining of "photography" is irrelevant. The origin of the words "illustration" and "draw" do not change their current usages in the slightest.

The ideas I took from this week:

- The way that the members of the Scientific Revolution saw themselves taking up the torch passed by the Greeks. They respected those who came earlier, but their theories weren't sacrosanct, it was the new generation's job to prove the Greeks' theories right or wrong. It's not offensive to question and prove something wrong.

- The way the scientists coalesced into academies and created an international community, the Republic of Letters. An analogous movement today may be newsletters, who knows? Also that both Hooke and Galileo received funding for general research and inventions.

- The importance of a shared language. There is a beauty about using simple language is that people tried many different ways of creating photography, but they were all connected by the concept that they were use created using light. However complicated the process actually became, it could be distilled down to a single simple word. As my mentor Joe Howard always says, "be obvious."

- The same idea of "writing with light" turns into photography where the light is the writing implement, whereas in illustration, light is the result of the writing. I had honestly never thought of illustration as light before, so this changes my view on it.

- Understanding the original process (like how they used to do illumination) often explains words whose original meanings are no longer relevant. This isn't a new thought, but it surprises me every single time I encounter it.